Coastal Louisiana is the drainage gateway to the Gulf of Mexico for the Lower Mississippi River Watershed. Southern Louisiana contains approximately 40 percent of the coastal wetlands found in the contiguous 48 states. The coastal system is comprised of the Mississippi Deltaic Plain in the east and the Chenier Plain in the west.

Coastal Louisiana is the drainage gateway to the Gulf of Mexico for the Lower Mississippi River Watershed. Southern Louisiana contains approximately 40 percent of the coastal wetlands found in the contiguous 48 states. The coastal system is comprised of the Mississippi Deltaic Plain in the east and the Chenier Plain in the west.

Why is this system important?

The wetlands of the Louisiana coast provide habitat for a variety of land and aquatic life and are the breeding ground and nurs eries for thousands of species of wildlife including the bald eagle. The ecosystem provides migratory habitat for millions of waterfowl Map each year. Threatened and endangered species that rely on Coastal Louisiana include sturgeon, sea turtles, the West Indian manatee, and the piping plover. The coastal zone is over 8,277 square miles and inhabited by roughly half of Louisiana’s population – over 2 million people. The coast is home to unique cultures made up of people whose way of life is directly connected to the bayous and wetlands. Louisiana’s economy is dependent on the industries that rely on the coast, including oil and gas production, shipping, seafood, hunting, fur harvesting, and tourism; accounting for up to 1.7 million jobs and approximately $35.7 billion in economic output. For example, Louisiana accounts for roughly 75 percent of fish and shellfish from the Gulf of Mexico and 28 percent of total volume of United States fisheries with a value of about $1 billion annually. Louisiana ranks among the top in the United States in crude oil and natural gas production and the Port of South Louisiana is one of the ten busiest ports in the world by cargo volume.

eries for thousands of species of wildlife including the bald eagle. The ecosystem provides migratory habitat for millions of waterfowl Map each year. Threatened and endangered species that rely on Coastal Louisiana include sturgeon, sea turtles, the West Indian manatee, and the piping plover. The coastal zone is over 8,277 square miles and inhabited by roughly half of Louisiana’s population – over 2 million people. The coast is home to unique cultures made up of people whose way of life is directly connected to the bayous and wetlands. Louisiana’s economy is dependent on the industries that rely on the coast, including oil and gas production, shipping, seafood, hunting, fur harvesting, and tourism; accounting for up to 1.7 million jobs and approximately $35.7 billion in economic output. For example, Louisiana accounts for roughly 75 percent of fish and shellfish from the Gulf of Mexico and 28 percent of total volume of United States fisheries with a value of about $1 billion annually. Louisiana ranks among the top in the United States in crude oil and natural gas production and the Port of South Louisiana is one of the ten busiest ports in the world by cargo volume.

What are major challenges?

Coastal Louisiana has experienced dramatic land loss since at least the 1930’s. A combination of natural processes and human activities has resulted in loss of over 1,880 square miles since the 1930’s, and a current land loss rate of 16.6 square miles per year. Not only has this land loss resulted in increased environmental, economic, and social vulnerability, but these vulnerabilities have been compounded by multiple disasters, including hurricanes, river floods, and the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, all of which have had a significant impact on the coastal communities in Louisiana and other Gulf coast states. Another challenge includes excess nutrients from the upper Mississippi River watershed that contribute to the “dead zone”, or a low-oxygen hypoxic area along the coast that is toxic to marine life. In 2016, the area reached about 5,898 square miles, an area about the size of Connecticut. Global warming will also bring more extreme weather events, and exacerbate land loss from sea level rise.

How is restoration and scientific research organized?

Several State and federal restoration programs are currently in place. The Coastal Wetlands Planning, Protection, and Restoration Act of 1990 is federal legislation designed to identify, plan, and fund coastal wetlands restoration projects to provide for long-term conservation. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and the State of Louisiana initiated the Louisiana Coastal Area (LCA) Comprehensive Coastwide Ecosystem Restoration Study in 2003. Following hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, the Louisiana Legislature created the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA) and tasked it with coordinating the local, State, and federal efforts to achieve comprehensive coastal protection and restoration. To accomplish these goals, the CPRA was charged with developing a Coastal Master Plan to guide work toward a sustainable coast. Scientific research on coastal Louisiana has been funded by Louisiana Sea Grant and others. The Mississippi River Hydrodynamic and Delta Management Study under the LCA program included research and model development to better understand the dynamics of the lower Mississippi River and the estuarine basins. The CPRA Applied Research Program ran for several years and funded research projects in support of implementation of the Coastal Master Plan. CPRA also sponsors a Coastal Science Assistantship Program (CSAP) which funds graduate student research. Many other government, non-government, academic, and private institutions participate in research and restoration efforts. The Water Institute of the Gulf, named the Louisiana Center of Excellence under the RESTORE Act, is a nonprofit institute that conducts research and links academic, public, and private research to increase the understanding of human influences to the coastal water systems and develops tools to assist in ecosystem restoration planning.

How is scientific research funded?

Broadly, a range of agencies and organizations provide funding for scientific research in Coastal Louisiana and, like the other systems, it is very difficult to find funding information in general for total research, restoration, and protection efforts. A legislative audit found for FY2008 – 2015, federal agencies provided $10.276 billion in funding for protection and restoration projects to CPRA; average annual funding has been $1.285 billion.[7] State agencies for FY2008 – 2015 provided in total $1.615 billion for CPRA protection and restoration projects, and on average $202 million. Of note, these figures do not include funds from the oil spill settlement, which were reported separately.

Scientific research is often leveraged as part of restoration project development and refinement. CPRA’s three-year protected budget through FY2019 is $1.5 billion, with over $96 million identified as part of adaptive management. This includes, for example, $325,000 per year for the CSAP and $6.4 million for Data Management. Under the RESTORE Act, Centers of Excellence across the Gulf coast will receive 2.5 percent of Trust Fund principal; 0.5 percent goes to Louisiana or about $4 million from the Transocean and about $0.6 million from the Anadarko settlements. It is expected that the gross allocation to Louisiana for the Center of Excellence will amount to $26.6 million through 2031. Scientific research will be funded across several different organizations including the Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Council, the National Academy of Sciences, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) RESTORE Science Program.

| Restore the Gulf

Following the Deepwater Horizon spill in 2010, many investigation and restoration efforts took place, including the establishment of the Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Council (GCERC*) in 2012 by the RESTORE Act (Act). The Act dedicates 80 percent of civil and administrative penalties paid under the Clean Water Act, to the Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund (Trust Fund) for ecosystem restoration, economic recovery, tourism promotion, and science to benefit the Gulf Coast Region—defined as land within the coastal zones (CZMA 1972), adjacent land, water, and watersheds within 25 miles of the coastal zone, and all federal waters in the Gulf of Mexico. The GCERC will oversee approximately $3.2 billion over the next 15 years, which is 60 percent of the Trust Fund. The Act requires the GCERC to “undertake projects and programs, using the best available science that would restore and protect the natural resources, ecosystems, fisheries, marine and wildlife habitats, beaches, coastal wetlands, and economy of the Gulf Coast.” In addition, the GCERC is committed to science-based decision-making, delivering results, and measuring impacts. *GCERC’s effort is in addition to the restoration of natural resources injured by the spill that is being accomplished through a separate Natural Resource Damage Assessment under the Oil Pollution Act. A third and related Gulf restoration effort is administered by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation using settlement funds from criminal charges against BP and Transocean Deepwater, Inc. |

Coastal Louisiana Presentation

Coastal Louisiana Presentation

Presenter: Dr. Denise Reed, Chief Scientist, The Water Institute of the Gulf. Research interests include coastal restoration and planning, role of human activities in coastal systems, sea level rise, adaptive management and modeling.

Coastal Louisiana and the delta of the Mississippi River are a very young landscape that was built by the Mississippi River over the last 6,000-7,000 years through the process of delta evolution.

It extends from the border with Texas on the west to the border of the Mississippi to the east. It’s largely still a natural ecosystem, and has not been altered the same way the California Bay-Delta has. There are swamps, marshes, and millions of acres of wetlands; some in good shape, others in not-so-good shape. There are low-lying barrier beaches and islands around the Gulf’s shore line which are threatened by hurricanes and other events.

The Louisiana coast is a place where people live and work. It’s known as a sportsman’s paradise for recreational fishing, as well for its culture and environment. People live in communities stretched out along the Bayou ridges and along the higher land and have lived there for centuries. Some of those communities have moved over the years in response to hurricane impacts and many of them now survive behind levees and structures to protect them. It’s also a working coast with the oil and gas industry being a key player in coastal issues for the last 80 years. Commercial fishing is also a very important part of the ecosystem.

The main issue facing the Louisiana coast is land loss; wetlands and barrier islands are being lost to open water – nearly 2000 square miles since 1932. “So something that was a wetland, a barrier island, or a natural land form has been converted to open water,” said Dr. Reed. “This is not land lost to golf courses and Walmarts. This is land lost to open water.”

The main issue facing the Louisiana coast is land loss; wetlands and barrier islands are being lost to open water – nearly 2000 square miles since 1932. “So something that was a wetland, a barrier island, or a natural land form has been converted to open water,” said Dr. Reed. “This is not land lost to golf courses and Walmarts. This is land lost to open water.”

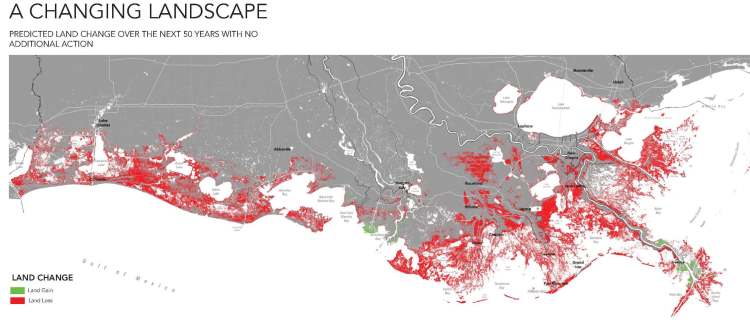

Dr. Reed presented a map showing the land loss that has occurred along the Louisiana coastline.

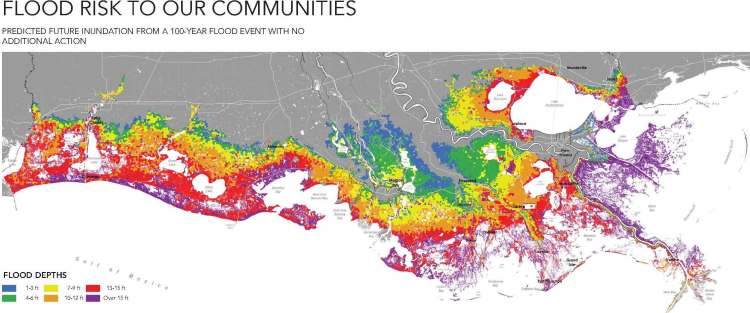

There is also the underlying issue of people and economy on the coast and the threat of hurricane storm surges. Dr. Reed presented a map showing the prediction of how deep the water would be for the hundred-year coastal flood event – not from riverine flooding but from storm surge flooding coming in from the Gulf of Mexico anywhere from 5-25 feet. Economic damages could be $7.7 to $23.4 billion by 2061.

One of the key contributions that science has been able to make to the discourse around Coastal Louisiana is to use the science and knowledge about the system not to describe its current status or how it’s changed from the past; but to think about what it’s going to look in the future, said Dr. Reed. “This idea of predicting and thinking ahead in order that policy and management decisions can be appropriately laid out in advance, as opposed to being reactive, which is very much the kind of Hurricane Katrina story of New Orleans, is I think one of the key roles of science in Louisiana and one of the key roles in large scale ecosystem management across the country.”

Dr. Reed then presented a draft map from the 2017 Coastal Master Plan that shows the prediction of what will happen in Coastal Louisiana in 50 years with sea level rise if no action is taken. “This is the context for planning,” Dr. Reed said. “All of the red on here would be lost. That means the Gulf of Mexico is at the door of Lake Charles. There is very little out port around New Orleans left.”

Another role of science besides communicating what could happen is to also help think scientifically about what the options are. Is there anything we can do about this? How can we use our science and our understanding of how the system works to prevent this happening? Can we prevent it happening and to what degree and where? “The policy decisions are going to be about investments and choices, but the science can really be about what can or could be done,” said Dr. Reed.

This issue of land loss is not new; they’ve been working on it for a while. When Dr. Reed began working in Louisiana in 1986, there was recognition of the issue and a grassroots effort to try to mobilize some investments and make some policy decisions to take some action. In 1990, the Coastal Wetlands Planning Protection and Restoration Act was passed; it was a federal statute which provides about $40-50 million a year for coastal restoration in Louisiana from the Small Engine Gas Tax and therefore it is independent of federal appropriations. The Act focused on vegetative wetlands on a project by project basis. It began as a comprehensive approach, but was scaled down to individual projects. It focused on protection and multi-criteria decision analysis.

That led to a comprehensive plan in 1993, which Dr. Reed described as ‘a wish list of projects.’ “A realization came out of that process in the early ’90s where we realized that $40-50 million a year was just not making any difference in this problem at all,” she said. “In the mid ’90s, there was an effort to do more of a strategic planning process to really think about what the coast needed and start to play offense rather than defense in trying to hold back the sea. Let’s see what we can do to actually get this system functioning again.”

In 1998, Louisiana’s Comprehensive Plan for a Sustainable Coast was developed in 18 months using existing information. The plan recognized the challenges and tradeoffs and was much more solidly scientifically based in general understanding; it brought decades of research on the coast to bear in terms of the underlying thinking about what needed to be done. It was very much strategic, but it wasn’t a plan that could be readily implemented. “We did a back of the envelope price tag for the things we were discussing and it came to $14 billion,” Dr. Reed said.

In 1998, Louisiana’s Comprehensive Plan for a Sustainable Coast was developed in 18 months using existing information. The plan recognized the challenges and tradeoffs and was much more solidly scientifically based in general understanding; it brought decades of research on the coast to bear in terms of the underlying thinking about what needed to be done. It was very much strategic, but it wasn’t a plan that could be readily implemented. “We did a back of the envelope price tag for the things we were discussing and it came to $14 billion,” Dr. Reed said.

In 2004, the Louisiana Coastal Area Plan articulated projects in a little bit more detail at a cost of $11 to $20 billion. “That draft documentation was sent to Washington, but frankly nobody in the administration in Washington had the stomach for that kind of program to be authorized at that point,” Dr. Reed said. “It was very much a scaled down program by the time it was authorized, down to $2 billion, and again, really a selection of projects.”

Post-Katrina, efforts by the USACE were focused more on protection rather than restoration of the ecosystem. The state combined the program that was working on restoration of the ecosystem and coastal land loss with the program that was designed to protect people from storm surge flooding. The state also called for a comprehensive master plan to be developed, which was to be updated by statute every five years. The first plan was developed in 2007, about a year after Katrina. “It was very strategic,” she said. “It was kind of a chicken in every pot, everybody’s got something in that plan and again, it wasn’t a plan that could be implemented.”

The governor then laid out a challenge to the scientific community. “He said, ‘Everybody is coming to my door saying I want this project, I want that project… Which one should we do? Are they all good? How do we work out what are the keepers, which ones to do first?’” Dr. Reed said. “This challenge was presented to several of us who had been involved in these plans over the years to think about how to do it.”

The 2012 Coastal Master Plan was built on science and engineering; it evaluated hundreds of project concepts and identified the investments that would pay off in the long run. They are currently working on the 2017 update. The plan had specific objectives. “It’s not just any old knowledge – it’s about tuning what we know about the system to evaluate different ideas about what can be done relative to some very specific objectives,” Dr. Reed said. “I think one of the things that had confounded some of those earlier planning efforts was a lack of sufficiently specific objectives. We had gone through a long planning effort on where an objective was improved fish and wildlife habitat. Who’s going to object to that?”

The 2012 Coastal Master Plan was built on science and engineering; it evaluated hundreds of project concepts and identified the investments that would pay off in the long run. They are currently working on the 2017 update. The plan had specific objectives. “It’s not just any old knowledge – it’s about tuning what we know about the system to evaluate different ideas about what can be done relative to some very specific objectives,” Dr. Reed said. “I think one of the things that had confounded some of those earlier planning efforts was a lack of sufficiently specific objectives. We had gone through a long planning effort on where an objective was improved fish and wildlife habitat. Who’s going to object to that?”

“But you can’t actually improve brown shrimp and alligators in the same place; you have to choose,” she continued. “We actually had to think about how we could use our scientific knowledge about the system in a way that would enable the decision makers to make that kind of choice. Am I going to do an action that promotes alligators or am I going to do an action that promotes brown shrimp with their eyes wide open. I think that’s the role of science.”

The objectives of the 2012 plan were to reduce economic losses from storm-based flooding, to promote a sustainable coastal ecosystem by harnessing the processes of the natural system, to provide habitats suitable to support an array of commercial and recreational activities coast-wide; to sustain Louisiana’s unique heritage and culture; and to provide a working coast to support industry.

A group of scientists were assembled to evaluate the projects, and what came out at the end were a series of projects all along the coast that if they were all to be implemented, the costs would be $50 billion in 2010 dollars. “One of the other pieces of this was this gradual recognition over a period of 20 years or so, was that the devil was really in the details; understanding the details and the scientific understanding of the system and its dynamics and how those need to be changed in order to get a more optimistic future,” Dr. Reed said. “That then comes with a substantially increasing price tag.”

Dr. Reed then turned to the question of their science infrastructure. “How do we organize ourselves to do this? Well, not very well is probably the answer,” she acknowledged. “In an ad hoc manner, we’ve been lucky in the way in which we as a scientific community have been able to contribute.”

Dr. Reed then turned to the question of their science infrastructure. “How do we organize ourselves to do this? Well, not very well is probably the answer,” she acknowledged. “In an ad hoc manner, we’ve been lucky in the way in which we as a scientific community have been able to contribute.”

Science is conducted by universities, agencies such as the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), research institutes, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs); a lot of cutting-edge science research is being done in the private sector as well. “Even though I can see all of these people making a contribution, it’s not obvious that there is any real coordination except around any one specific issue,” she said. “There isn’t one way we come together.”

Dr. Reed said they are fortunate to have decades of research; being on the delta of the sixth largest river in the world really has made it a scientific point of interest for decades. They were able to leverage all of the previous research, understanding, and knowledge base. “l think we’re actually able to leverage the knowledge base from university research better than we are able to leverage the current skills of the university research community,” she said. “This is really not about me or any of my colleagues as much as it is about the work that has come before.”

The very first act, the 1990 Coastal Wetlands Planning Protection and Restoration Act, was focused on vegetative wetlands, called for a scientific evaluation to be conducted every three years. It established the Coastwide Reference Monitoring System (CRMS), an extensive coastal monitoring system focused on vegetative wetlands. There were 390 monitoring stations across the coastal wetlands of Louisiana, founded by for the most part by Act, which continues to do work after 20 years and continues to provide tens of millions of dollars for restoration every year.

They are now thinking about moving beyond just a vegetative wetlands monitoring system and establishing a system-wide assessment and monitoring program. “The need to think about all different aspects of our coastal system is now something that is very much on the radar screen of the agencies,” said Dr. Reed. “We’ve actually have some initiatives within the agency teams working on coastal Louisiana that are focused on providing a really important baseline of information.”

They are now thinking about moving beyond just a vegetative wetlands monitoring system and establishing a system-wide assessment and monitoring program. “The need to think about all different aspects of our coastal system is now something that is very much on the radar screen of the agencies,” said Dr. Reed. “We’ve actually have some initiatives within the agency teams working on coastal Louisiana that are focused on providing a really important baseline of information.”

With regards to funding, even though they are not well organized, they do quite well taking advantage of different funding sources. Funding for university research is thin and there are no dedicated funds; the Sea Grant program has done a valiant effort over the years with fairly limited resources of about $2 million a year. In those early years, some of the early work on the Mississippi delta was funded by the Office of Naval Research who wanted to understand delta processes; a lot of it was funded by oil and gas companies who wanted to understand deltas, reservoirs and sedimentary dynamics. Those resources are not ongoing or necessarily currently available.

The programmatic monitoring is important for providing a solid baseline; those 390 stations now have produced a very rich and available pool of data across the coast. “We now actually have opportunities to develop and apply science, not within the context of a science program or a specifically science labeled entity or activity, but within the context of actually moving the restoration forward in project specific opportunities,” Dr. Reed said.

The 2017 Coastal Master Plan has three basic elements: Projects to be evaluated, predictive modeling, and a planning tool, which is an optimization or an applied math scheme. So far, it has cost about $10 million over the last three to four years, Dr. Reed said. A lot of the funding goes through the Water Institute and 14 different subcontractors. The Water Institute has an advisory panel and includes expert review on key reports.

Dr. Reed explained when a project is included in the Master Plan, it’s a concept that’s risen to the top of the pile; it then has to go through detailed planning and engineering and design before any kind of dirt is moved. There is modeling, permits, and a decision to advance. “What you see in here is an awful lot of analysis being done that is really an opportunity for the scientific community and for science to come together to inform the decision,” said Dr. Reed. “A lot of funding is associated with that.”

Dr. Reed explained when a project is included in the Master Plan, it’s a concept that’s risen to the top of the pile; it then has to go through detailed planning and engineering and design before any kind of dirt is moved. There is modeling, permits, and a decision to advance. “What you see in here is an awful lot of analysis being done that is really an opportunity for the scientific community and for science to come together to inform the decision,” said Dr. Reed. “A lot of funding is associated with that.”

Another source of significant funding for building projects and for science has come as a result of the Deepwater Horizon incident in 2010 in the form of civil penalties, criminal penalties, and natural resource damages. The funding is split between five states on the Gulf Coast; each state has a Center of Excellence that receives $133 million over 15 years. The NOAA has a science program for research relative to Gulf restoration that also has $133 million which is to be distributed over 15 years through a competitive grant process. The project money to develop and apply science within the context of projects is $1.3 billion from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. Louisiana is also receiving some of the natural resource damage assessments.

Dr. Reed noted that most of the available resources are to build projects. The Louisiana Center of Excellence is about to issue a request for proposals for $3 million. “That’s the biggest RFP for research from coastal Louisiana that I ever remember in 30 years,” she said. “It’s not enough but hopefully we’ll be able to make a dent in this. This is research to support the implementation of the Coastal Master Plan.”

In terms of making science helpful and making a difference to a decision maker, modeling has been what has enabled them to come together and to think about the future. “In the Master Plan, we had to evaluate hundreds of different projects and we did that specifically by developing models,” she said. “We had specific things we had to analyze, too. We had to analyze about land. We had to analyze about expected annual damages. We needed to really develop a set of tools and apply information to a very specific end that the Coastal Production Restoration Authority was looking for.”

They built a specific modeling approach to evaluate the projects having learned from earlier efforts to use existing models in the early 2000s that were not successful because the research models that were being used at the time weren’t necessarily applicable to the application at hand.

The modeling approach they built was a simplified coastal model that covers the whole coast and a lot of process interactions within the natural environment, such as open water processes, barrier island processes, wetland processes, exchanges of salt or fluctuations in water level, and movements of sediment. The physics is simplified; it is essentially mass balance approach. “This is not our best, most sophisticated model,” said Dr. Reed. “It is one that is tailored to this very specific purpose that we had in mind. It’s only been possible because we have data from those 390 monitoring stations across the coast of wetlands off the coast.”

The modeling approach they built was a simplified coastal model that covers the whole coast and a lot of process interactions within the natural environment, such as open water processes, barrier island processes, wetland processes, exchanges of salt or fluctuations in water level, and movements of sediment. The physics is simplified; it is essentially mass balance approach. “This is not our best, most sophisticated model,” said Dr. Reed. “It is one that is tailored to this very specific purpose that we had in mind. It’s only been possible because we have data from those 390 monitoring stations across the coast of wetlands off the coast.”

Dr. Reed acknowledged there were a lot of issues with how they resolved different spatial scales of resolution. “There are a lot of assumptions in here. I probably know where all the challenges are in it but it certainly seems to meet the purpose. It was really a key thing underlying the 2012 Coastal Master Plan and will be the key thing underlying the 2017 Master Plan. We have been able to continue to develop it because it has been so useful. That $10 million for the 2017 plan would not have been invested in the team unless we had actually shown that we could provide evaluations for the 2012 plan.”

A lot of research has been done on deltas, so the job was to leverage that information into the kind of detailed level analysis needed for engineering design. “These opportunities have forced us or allowed us to work across disciplines very closely,” said Dr. Reed. “It has been uncomfortable, but it has been the secret to success.”

They were asked questions, such as ‘Are these projects effective? ‘Can they build land?’ “We know conceptually they can; we know a lot about deltas and how they work,” said Dr. Reed. “But how much land would you actually build with 75,000 CFS at this location versus that location? We can predict what would happen if we don’t do the project. Then, if we do four of these diversions, what do we get? If we only do two of them, what do we get? We’re talking about billion dollars of investments to build these things, and so the investment in this kind of team building and modeling for this kind of science and application here is really a very minor part of the overall project cost. I think it’s gone a long way to moving these things forward in the decision-making framework.”

Dr. Reed said that being asked questions that are of that scope and having resources being made available and at a kind of scale of magnitude that is reasonable. The model was built with a large team of people in about 18 months for around $3-5 million. “It was doable,” she said.

Dr. Reed said that being asked questions that are of that scope and having resources being made available and at a kind of scale of magnitude that is reasonable. The model was built with a large team of people in about 18 months for around $3-5 million. “It was doable,” she said.

In terms of communication, Dr. Reed said there are few specific mechanisms; it’s very top down. There are many people working on the master plan: federal agencies, state agencies, universities, and the private sector. “The boards are held pretty narrowly by the state,” Dr. Reed said. “It says on here that the CPRA and the Water Institute of the Gulf directs and coordinates model improvements and analysis, but I’d say CPRA directs and we coordinate.”

One of the challenges and the opportunities is with all the knowledge they already have about the system, making sure they can still be innovative and creative. For funds associated with projects and planning, innovation and risk can be constrained. “Having opportunities for science and scientists to advance, expand, and increase thinking in addition to really applying it in a very exciting way is something that we don’t really have,” she said. “Perhaps because I am in the middle of this, it feels very top-down sometimes.”

They have a successful biennial science conference modeled after the Bay-Delta’s and the Everglades which is a great venue for sharing. There are a few occasions where there is public engagement on science, but Dr. Reed acknowledged there weren’t very many of them. They have started to do webinars and give presentations to stakeholder groups.

In terms of coproduction, Dr. Reed said working in the context of moving projects from idea to plan to eventually moving dirt on the ground and to actually move 75,000 cfs of water requires they work very closely with the private sector. “We are not doing the engineering,” she said. “There were engineers working on this project on the science side and on the analytical side, but they’re not really doing engineering, so we’re working very closely with the private sector design firms that are doing this. Therefore, we’re answering pretty specific questions. This is a good collaboration.”

Dr. Reed said they do a lot of external expert engagement, reports, and reviews. One approach they have found really useful is the ‘over-the-shoulder review.’ “You don’t wait until the end to get people in; you actually have people looking at what you’re doing on a regular basis and providing advice and guidance along the way,” she said. “That’s pretty helpful.”

Dr. Reed said the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA) does a fantastic job at with the Coastal Information Management System (CIMS) which makes the monitoring data available.

Dr. Reed said the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA) does a fantastic job at with the Coastal Information Management System (CIMS) which makes the monitoring data available.

Dr. Reed then gave her closing thoughts. There are no formal mechanisms. “We’ve tried a lot over the years to get university collaboration and coordination,” she said. “A lot of the university scientists have recognized that this is the research opportunity of our lifetime, of multiple generations, to work on this. How can we as a university community come together and provide a collective platform for those federal and state agencies who are trying to address this problem? We have not been successful at that. We have tried several times. That lack of success is one of the reasons why the Water Institute was established, as a kind of convening body as much as anything else.”

There are few opportunities to synthesize, Dr. Reed said. “Here in the Bay-Delta, the kind of state of knowledge synthesis work that you’ve been able to do on a regular basis – we have not been able to do that. That is something which would be very valuable and would really help with communication. I think a lot of the folks who are very concerned about the problems in coastal Louisiana don’t really understand how much we know about it and what we don’t know about it.”

The community of scientists and researchers in coastal Louisiana are very active in going after standard things like National Science Foundation reviews. “If you’ve been on a review panel for the National Science Foundation, or you’ve been subject to review by the National Science Foundation, you know that the reviewers are not always interested in the kind of things that it takes to actually move a restoration forward,” Dr. Reed said. “It’s challenging.”

“The thing we have yet to realize and that we are finally getting serious about is program level adaptive management,” she said. “Come back in three years and I would be happy to have that discussion about whether or not we’ve actually really managed to use that as a unifying concept for the science enterprise. I think there is a lot of promise in that, depending on how we think about it. That for me will be the real test, of how that really plays out as we move forward.”

“We’ve got billions of dollars to spend on this coast. We have a responsibility as a society to use that wisely, and to have those decisions informed by science and to have that as a continuing process, and so, that is going to be a watch-this-space for coastal Louisiana,” concluded Dr. Reed.

Question and Answer

Question and Answer

Question: Could you tell us a little more about that integrated compartment model, how it was started, who funded it and how long it lasted?

Dr. Reed: One of the reasons I stepped through all those previous plans was that there were a number of us in the university community coastal researchers who had been trying over the years to engage in these processes and try to help. Certainly, in the Louisiana coastal area study in 2004, they really tried to apply what research models were available.

When this challenge came up of how to work out which of the best projects to do, I can distinctly remember having a conversation with one of my colleagues at the University of Louisiana, Lafayette, saying if we’re going to do this, we can’t do it the way we’ve done it before. We have to simplify. … It’s not quite as fulfilling as doing that really well defined, very detailed, very process based research type modeling. It’s not as fulfilling as that, but are you interested in doing it?

There were enough folks that were interested in doing it, and the state at that time, the folks in the governor’s office were sufficiently motivated that for the 2012 coastal master plan, the modeling probably was similarly of the order of $10 million but we were building these things from scratch at that point. The money came from the state. Everybody who worked on it, including the federal agencies, was paid to work on it. … It was the same money that could otherwise have gone to building our project, went to doing this. It was money in the state trust fund.

Question: Are those outcomes, those recommended projects that points to diversion and volumes, are those generally accepted in the region or is it highly controversial? It seems like it was pretty much, ‘here’s what we’re going to do; here’s what makes sense.’ I’m just curious if other people were saying no. Is it really a contentious issue for the region?”

Dr. Reed: The story with the diversions is that the idea had been in all the previous plans. The idea had been in the 2012 plan; the simple compartment model analysis identified that four or five of them were worth doing. They weren’t the only things in the plan, but they rose to the top. There’s another, more detailed set of analysis… At one point, it was kind of complex slide with all these decision boxes on, which was really the state trying to move to a decision on what they were going to do with these. The current thinking of the state government, as articulated very clearly by the governor’s coastal lead was we are going to do these diversions. We are going to work though some of these issues, but we are going to do the diversions.

This is also a story of evolving sides. When you do a simple model, you can’t get into all of the details; you have a generalized picture of what’s going to happen. As we get more and more into the details of these things, we apply more sophisticated tools and can look at things in more detail. We explore actually how you operate a diversion like this to maximize land building. We are now looking at optimizing the operation to maximize sediment delivery and minimize freshwater input and how you can do that at different times of year. There is this continuing role for the analysis. It’s not like, okay it’s in the master plan, now the engineers are going to go on and build it. As you get into all of these further issues, then there is more and more analysis needed.

I was saying earlier that sometimes I felt like the boards were little constrained. That scientists and expert panels – these external people were making very good suggestions and they were being ignored. That kind of social impact analysis side of this, which is what is going to happen to commercial fishery and the people whose livelihoods depend on it, has not yet been analyzed in a lot of detail. The EIS for those projects is just going out and being competed. The idea is that the social impact assessment part of the EIS will be quite thorough, but that has yet to be proven.

I didn’t spend a lot of time talking about whether the social science came into this. There is a large part of the master plan which is about hurricane storm damage risk reduction, and things like that where there is economic analysis of storm damages done. That’s not quite the same as livelihoods and displaced fisheries.

Question: Are these being designed as explicit adaptive management experiments? I was also curious who the decision makers are. That’s an issue we have in adaptive management around here; who are the decision makers, anyway?

Dr. Reed: There’s only one Mississippi River and there’s only one basin, so this is not going to be an adaptive management experiment. We are not going to experiment with a billion dollars of valuable resources. That is not the terminology that will be used. I think these are great opportunities for us, because there is a knob, right? You can turn it on and you can turn it off. You can have it half-open or you can have it full-open.

I think there is a great opportunity with the development of the operational plans, and the master manual or whatever there will be for these, to ensure that the decision making is nimble in response to changing system conditions. One thing we have developed at the institute… is we’ve developed a real-time forecasting system for those basins… We have enough real time streams of data coming from some of these stations across the coast that we can get it operational so that we can look at what the water level and salinity conditions, at least in those basins, will be for the next week if you do this, or for the next week if you do that.

This is something where if people want to be able to make real-time adaptive management decisions, the science is there. We can do that. We haven’t actually got funding to do that, yet, to actually make that operational but I do think that we are starting to move. Perhaps there’s controversy and discussion about how are these things going to be operated, and that may actually be the thing that stimulates the resources being made available for the scientific community to respond.

We would really like to move that into nutrients and harmful algal blooms. At the minute, we’re a bit limited by real-time data streams… those should be coming online soon. We have a little bit of foundation money from a private foundation to try and add that piece on. Some of this is like entrepreneurial science; you’re doing it because you think it’s going to be really useful and then you’re hoping somebody’s going to pick it up and carry it on. As yet, they haven’t done that.

There are no experiments. I am not going to say that they are experiments. I shouldn’t have even said the word, because, that’s just not an appropriate way of framing it within our system. This is not the time for experimentation; this is the time to build on our decades of science and knowledge about how the system works, and to actually implement a solution with the resources we happen to have available from Deepwater Horizon. It’s just an impossible discourse, to talk about it in that kind of theoretical scientific way.