by Robin Meadows

The San Francisco Bay-Delta is already among the most intensively studied ecosystems in the world. Now 18 experts are scrutinizing this system afresh in a committee convened by the National Academies at the request of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The stakes are high.

The Bay-Delta system drains about half of California’s surface water. Even so, there’s still not enough to meet the demands of water users―including farmers and hydroelectric power agencies―and the needs of salmon, Delta smelt, and other fish protected under the federal Endangered Species Act.

“Species aren’t doing well, and water deliveries and power generation aren’t doing well,” Mario Manzo, deputy manager of the Bureau of Reclamation’s Bay-Delta Office, told the National Academies committee at its first public meeting in January 2024.

The committee’s charge is to help bolster the science behind the operations of two massive water projects that divert flows from the Bay-Delta system via networks of dams, reservoirs and canals. One is the Central Valley Project, which spans 400 miles and is run by the Bureau of Reclamation; the other is the State Water Project, which spans 700 miles and is run by the California Department of Water Resources.

Together, these two closely-coordinated water projects supply millions of acres of farmland and nearly 30 million Californians, as well as protected wetlands in National Wildlife Refuges and California Wildlife Areas.

The challenge of providing flows for people while also protecting fish is made more daunting by the increasing uncertainty of California’s water supply as the world warms. “This last decade did not look like the one before it,” state climatologist Michael Anderson told the committee. “The question is: well then, how much different is the next decade going to be?” By the end of the century, California will likely undergo more extreme deluges and droughts, and lose two-thirds of the snowpack that, as it melts, gets the state through the summer dry season.

A WICKED PROBLEM

The causes of fish declines in the Bay-Delta system―from the loss of freshwater flows and wetland habitats to the rise of nonnative species and contaminants―are clear. But the solutions are not, and agency staffers welcome the National Academies committee’s help.

“We’re really looking forward to your work on our wicked problem,” Bureau of Reclamation fish biologist Josh Israel told the committee, referencing a term ecologists apply to issues that are too complex for single solutions.

“Wicked problems are multi-faceted so there’s no silver bullet,” explains Samuel Luoma, a University of California, Davis research ecologist and lead author of a 2015 paper detailing the Bay-Delta’s many challenges. “The Bay-Delta has multiple endangered species with multiple stressors, including dams, paucity of food for fish, and climate change―we can’t say ‘if only we did this, the problem would go away.’”

Dams block access to the mountain streams where salmon once spawned, and also disrupt the natural stream flows that California’s fish are adapted to and depend on. “It’s hard to be a critter in the Central Valley Project,” the Bureau of Reclamation’s Manzo told the committee.

Extensive wetland loss in the Delta has resulted in a dearth of zooplankton, tiny creatures that young salmon and Delta smelt eat. And climate change increases the likelihood of extreme droughts, further pitting farmers against fish.

One root of the Bay-Delta system problem is that historical approaches to water management don’t work well today. As Luoma and colleagues wrote in their 2015 paper, “California’s water problems can no longer be solved through supply management and traditional engineering solutions alone.”

While the foundation of California’s water supply is crumbling as warming shrinks the snowpack, demand for surface water is rising. The latter is driven by population and economic growth coupled with restrictions in the state’s groundwater use, which were implemented for the first time ever under the 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act.

“We don’t have enough water for all the things we want to do in California,” Luoma says.

NATIONAL ACADEMIES REVIEWS

The National Academies, nonprofits operating under a congressional charter signed by President Lincoln, help the nation “study complex and sometimes contentious issues, reach consensus based on the evidence, and identify the best path forward.” In other words, they were basically instituted to help the nation deal with wicked problems.

This is the second time the federal government has asked the National Academies to weigh in on the Bay-Delta. Luoma, who served on the first such committee about 15 years ago, cautions against unrealistic expectations from the National Academies reviews.

“Sponsors may expect that this will make the science unassailable so they can justifiably move forward,” Luoma says. “The reality is probably not going to be that black and white.” Rather, National Academies reviews can assess the strengths of and spot gaps in existing scientific knowledge.

FEDERALLY-LISTED FISH IN THE BAY-DELTA SYSTEM

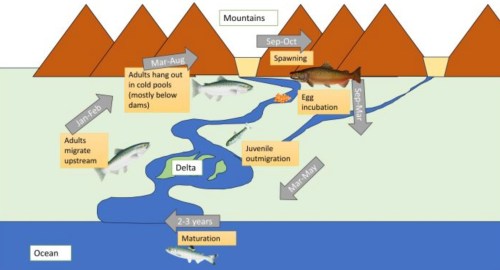

The Bay-Delta system is home to four species of federally listed fish. Two of the four runs of Chinook salmon that return from the ocean to spawn in the Bay-Delta system are listed under the federal Endangered Species Act: spring-run are threatened, and winter-run are endangered. California Central Valley steelhead trout, salmonids that likewise begin life in freshwater and migrate to the ocean as young fish, are federally threatened.

Delta smelt, which live only in the Delta, are born in freshwater and then migrate to brackish waters. Once plentiful, these small, translucent fish are now federally endangered, with so few remaining that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service hopes to shore up the wild population with releases of hatchery-raised fish.

Green sturgeon, which reach lengths of seven feet and live as long as 70 years, spend most of their lives in the ocean and return to freshwater every few years to spawn. Those that breed in the Sacramento River system are federally threatened, and UC Davis researchers think these fish might benefit from migration flows of freshwater like those currently released from reservoirs for salmon.

These four federally-listed fish species can have different water needs at different times of year and in different parts of the Bay-Delta system. California’s aquatic species adapted to natural flows that the water projects disrupted, and the Bay-Delta system is so engineered and altered that providing the environmental flows fish need is a challenge.

SAVING FISH FROM THE SOUTH DELTA PUMPS

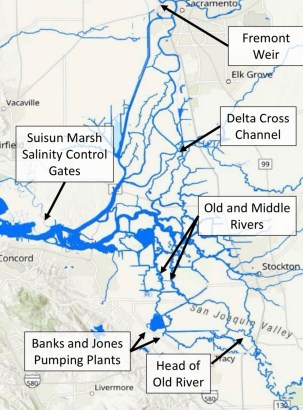

In the current Bay-Delta system review, the Bureau of Reclamation has asked the National Academies committee for help making three aspects of California’s water project operations more fish friendly. The first is flows in Old and Middle rivers, the main channels in the south Delta. Water in the Delta naturally flows into the San Francisco Bay and then out to sea. But this pattern is disrupted by the Central Valley Project and State Water Project, which export water from the south Delta via pumps.

Pulling water southward makes parts of Old and Middle rivers run backwards―that is, away from the ocean―during much of the year. These reverse flows can kill fish by leading them to the export facilities, and can also keep young salmonids from migrating out to sea.

“How can we keep fish out of the interior Delta and away from the pumps?” the Bureau of Reclamation’s Manzo asked the committee.

Approaches include limiting reverse flows in Old and Middle rivers to 5,000 cubic feet per second as well as managing these flows in real time. Limiting reverse flows entails slowing the pumps, which curtails water exports from the Delta.

The cost of this fish protection measure to the water supply is substantial, said David Mooney, manager of the Bureau of Reclamation’s Bay-Delta Office. “It’s reasonable for a water supply agency to try to refine that―to fully understand that water cost,” he told the National Academies committee.

Limiting Old and Middle river reverse flows also takes a lot of staff time. Mooney estimates that federal and state agencies collectively dedicate 20 to 40 staffers for half of each year to this effort. “This seems like a ripe area to help us develop science and make that an easier action to take place,” he said.

BOOSTING DELTA SMELT SURVIVAL

The Bureau of Reclamation also wants the committee to help find ways of protecting Delta smelt through the summer and fall. These all-but-gone fish hatch during the spring in freshwater on the inland side of the Delta, and then rear during the summer and fall in brackish waters on the San Francisco Bay side of the Delta. Young Delta smelt historically thrived in the vicinity of Suisun Marsh, which lies between the Bay and the Delta, but are in trouble today.

“Delta smelt don’t make it over the summer,” Mooney told the committee.

The big-picture thought is that the Delta smelt’s rearing grounds have too much salt and not enough food. Proposed actions include using gates to help keep salt water from the San Francisco Bay out of Suisun Marsh, and augmenting fish food with zooplankton from the north Delta. The latter would entail inundating the Yolo Bypass, a flood control structure built in a former floodplain of the Sacramento River.

But the nitty-gritty details of why young Delta smelt are dying, as well as how to keep them alive, remain to be tackled. “Having the panel help us think through this would be very helpful,” Mooney told the committee.

KEEPING WATER COLD FOR WINTER-RUN CHINOOK

The Bureau of Reclamation’s third ask of the National Academies committee is for help protecting winter-run chinook salmon. These fish spawn as far into the year as August and their last remaining spawning grounds are in the Sacramento River below Shasta Lake, which is part of the Central Valley Project.

The timing and location of spawning are a bad combination. Salmon need cold water but a scorching Central Valley summer can raise the river temperature enough to kill their eggs. In 2021, there wasn’t enough cold water left in Shasta Lake to bring the river temperature down and three-quarters of the winter-run chinook eggs perished.

This disaster prompted the Bureau of Reclamation to start saving a pool of cold water for the salmon in Shasta Lake from one year to the next. This win for fish is a loss for water users during droughts.

In 2022, the state’s fourth driest on record, the Bureau of Reclamation saved water for winter-run salmon by slashing water deliveries more than 80% to Reclamation District 108, which supplies irrigation water to nearly 48,000 acres of farmland in Colusa and Yolo counties. Agricultural damages topped $1 billion and more than 14,000 people lost their jobs, according to a report by UC Davis agricultural economists.

That said, the cold water pool in Shasta Lake may be all that stands between winter-run chinook and extinction. Reclamation District 108 is considering voluntary water cuts during critically dry summers, and sound science on diversion reductions is key to buy-in among water users. “Our wants include defensible criteria for protecting winter-run chinook,” Bureau of Reclamation fish biologist Israel told the National Academies committee.

NEXT STEPS

The National Academies committee meetings are held at various places around the state, and include tours of the water project operations in question as well as of affected habitats and ecosystems; the next meeting is scheduled for May 7 and 8 in Redding.

The committee will continue conducting its review of water project operations that affect fish in the Bay-Delta system over the next year and a half, and will submit a draft report that includes recommendations for the “highest priorities for improvement” in the fall of 2025.

After that, the Bureau of Reclamation has already committed to a second round of Bay-Delta system review by the National Academies, and may also sponsor ongoing biennial reviews. This approach is in line with former National Academies committee member Luoma’s take.

“The solution to the Bay-Delta problem lies in a continued battle to understand its complexities,” Luoma says.

OTHER AT-RISK FISH

Ashley Overhouse, Defenders of Wildlife’s Water Policy Advisor, hopes the National Academies committee will also consider the Bay-Delta system fish that lack federal protections but are nonetheless at risk. She’ll be able to address the committee formally during its May meeting, when the agenda will include a stakeholder panel.

“The decline of endangered species is the canary in the coal mine,” Overhouse says. “There are also declining aquatic species across the board.”

Chief among these is the longfin smelt, slim, silvery fish that live mostly in salty water and spawn in freshwater. Longfin smelt are already listed as threatened under the California Endangered Species Act. While not listed federally, in 2022 USFWS determined that listing the San Francisco Bay-Delta population as endangered was warranted.

Lenny Grimaldo of the state Department of Water Resources shares Overhouse’s concern about longfin smelt. “We definitely see them at our project facilities, probably in higher abundance than any other fish we salvage at the moment,” he told the National Academies committee. Both the state and federal water projects have systems designed to divert fish from water exported from the south Delta. These salvaged fish are then loaded into tanker trucks and transported to the western Delta.

Central Valley fall-run chinook are the mainstay of the state’s commercial salmon fishery. But even though hatcheries supply most of these fish, they have declined to the point that the commercial fishery was closed last year. “They’re not listed at all,” Overhouse says. “I’m concerned about fall-run chinook being a victim of lack of attention.”

California’s white sturgeon historically exceeded lengths of 20 feet and lifespans of a century, and were abundant enough to support a commercial fishery. But this population, which lives in the Bay-Delta and spawns in the Sacramento River, has declined by two-thirds since the early 2000s. “I’m concerned they’ll be overlooked in the review process,” Overhouse says.

Overhouse also hopes the National Academies committee will consider the National Wildlife Refuges and California Wildlife Areas that are supplied by the water projects. These managed wetlands include remnants of California’s once vast freshwater and tidal marshes that abounded with migratory birds. “They’re all that’s left,” she says. “They’re critical for habitat, flood control, and groundwater recharge.”

“Key reductions to some water contractors will probably be necessary for species to get their required water,” Overhouse continues. As someone whose family ranched and grew almonds near Winters for generations, she understands the impact of water cuts on farmers.

“It’s a really tough reality,” Overhouse says.