State water officials say California needs five consecutive winters like 2023 to recover from years of drought-induced overpumping.

By Natalie Hanson, Courthouse News Service

![]() An extraordinary water year brought much-needed relief to a drought-stricken Golden State, but experts say California needs several more exceptionally wet years to repair lingering damage to precious underground water supplies.

An extraordinary water year brought much-needed relief to a drought-stricken Golden State, but experts say California needs several more exceptionally wet years to repair lingering damage to precious underground water supplies.

The newest Semi-Annual Groundwater Conditions report — using the first annual data collected from groundwater sustainability agencies across 99 basins holding more than 90% of the state’s groundwater — indicates the state has gained 4.1 million acre-feet of water through underground recharge, nearly the total storage capacity of Shasta Lake. Meanwhile, underground storage improved by 8.7 million acre-feet.

Thanks to the surprise string of record-breaking storms, 2023 marked the first year since 2019 that agencies saw a jump in groundwater storage. State officials permitted local agencies to divert more than 1.2 million acre-feet of water toward groundwater recharge — a smart redistribution and banking of floodwater.

Thanks to the surprise string of record-breaking storms, 2023 marked the first year since 2019 that agencies saw a jump in groundwater storage. State officials permitted local agencies to divert more than 1.2 million acre-feet of water toward groundwater recharge — a smart redistribution and banking of floodwater.

Groundwater pumping also decreased significantly during 2023, helping to decrease the effects of a devastating multiyear drought. Some areas suffering from land subsidence saw a rebound in ground surface elevation thanks to reduced pumping from deep aquifers and improving groundwater storage, agencies reported. The hard-hit San Joaquin Valley accounted for more than half of the statewide reduction in groundwater extraction, as groundwater levels rose by more than 5 feet in 52% of monitored wells.

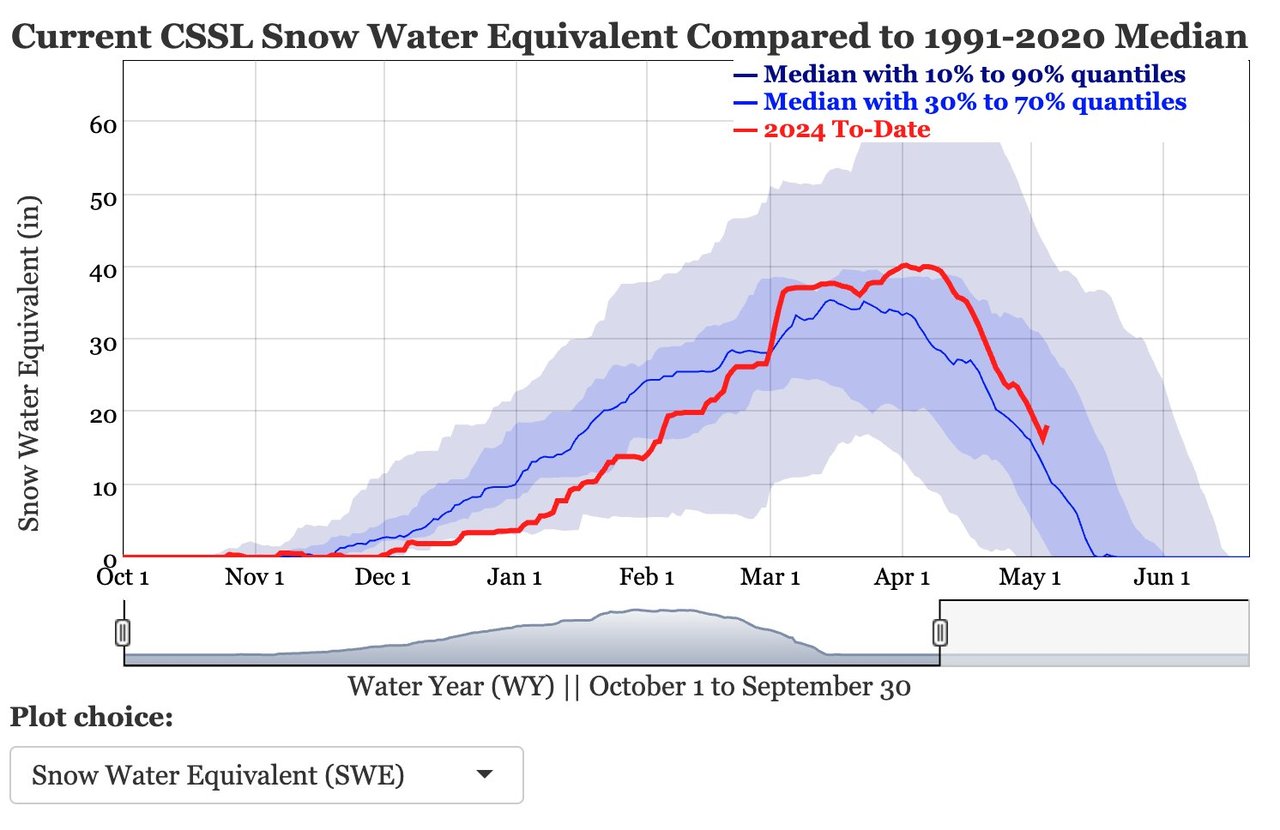

Monday’s report comes as winter storms continued into late spring. While 2024 has been far less wet than the previous year, experts say the state averted a snow drought following a string of cold, wet storms in March.

That good news has continued into May, as National Weather Services meteorologists in Sacramento reported Monday that many peaks in the north state received snow from a cold weather system over the weekend. Lower Mt. Lassen took first place with 31 inches, followed by Palisades Summit and Soda Springs at 26 and 22 inches, respectively.

University of California, Berkeley’s Central Sierra Snow Lab said in a post on X that Sunday marked a new peak in the state snowpack, bringing the state to 157% of its average snow water equivalent. That measurement helps state agencies determine how much water might come from the total snowpack, as snow melts during the warmer months and refreshes reservoirs, watersheds and underground reserves.

Water experts have said that snowfall late in the season can only increase the positive outlook. But while the last two rainy seasons have been good news for California’s groundwater basins, they say much work remains.

California’s long-term groundwater storage is still in a deficit by about 40 million acre-feet, largely due to over-pumping of ground aquifers by farmers during drought over the past two decades. State water scientists say five consecutive above-average water years like 2023 would be needed to fill that gap.

“We need to continue streamlining processes and investing in water management strategies and infrastructure, like stormwater capture and groundwater recharge, and enhanced water conveyance facilities like the Delta Conveyance Project,” the department’s Paul Gosselin, deputy director of sustainable water management, said.

“California is invested in preparing for weather extremes by maximizing the wet years to store as much water as possible in preparation for the dry years. The impressive recharge numbers in 2023 are the result of hard work by the local agencies combined with dedicated efforts from the state, but we must do more to be prepared to capture and store water when the wet years come.”

Since 2014, the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act has emphasized local control and requires local groundwater sustainability agencies to develop and implement plans that will bring basins into balanced conditions by 2040. The state can also take control if a local agency’s plan is declared out of compliance, which took place in April as state officials temporarily watch how much water is pumped from the ground in the Tulare Lake Subbasin.

Gosselin said the semiannual groundwater report helps state agencies assess conditions due to climate change, and how much groundwater California has, to make water management decisions for the future.