What are the cascading, overlapping, and compounding events caused by drought in the Delta? In early December, the California Council for Science and Technology brought together four experts who discussed the impact of drought on water quantity, water quality, ecosystem health, public health, agriculture, and more in the California Delta.

First, Sarah Brady, Deputy Director of the California Council for Science and Technology (CCST), introduced the Council and their Disaster Resilience initiatives. The Council is a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization established over 30 years ago by the Legislature to provide science and technology advice from the wealth of California’s outstanding academic and research institutions directly to policymakers.

“California is lucky to have such an incredible network of expertise,” said Ms. Brady. “Our job at CCST is to help amplify and translate the expertise in this network into actionable advice for policymakers. We do this through a number of mechanisms, including briefings like this one. We also host workshops, write peer-reviewed reports, and run the CCST Science Fellows Program, where we place Ph.D. scientists and engineers for a year of government service and leadership training in the executive branch and Legislature.”

As part of their mission, the CCST has launched Disaster Resilience initiatives to help the state better prepare for and respond to ongoing, complex, and intersecting disasters, including climate change, extreme heat, power outages, and the COVID 19 pandemic, which are radically disrupting the ways in which Californians live and work.

“These disruptions, while often destructive and painful, can provide us opportunities to redesign our systems to be more resilient and sustainable,” said Ms. Brady. “So through our Disaster Resilience initiative, we seek to deliver science and technology advice to reduce harm and improve the lives of all Californians. Today, we will be focusing on the compounding and cascading impacts of drought in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta and how addressing these impacts can help California meet its disaster resilience goals.”

Introduction

The moderator for the panel was Dr. Laurel Larsen, Delta Lead Scientist for the Delta Stewardship Council, Associate Professor of Geography and Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of California Berkeley, and an expert on hydroecology, landscape dynamics, and environmental restoration. She began with some opening remarks to set the stage.

“Drought in California has many negative effects on water availability and water quality to end users. In fact, typically, when we think about drought in California, we think about dry reservoirs, poor water quality, and wildfire. However, drought sets off a cascade of other impacts, as resource agencies and scientists have seen firsthand over the last decade. Some of these impacts were previously unforeseen, and some are long-lasting, persisting for years beyond the end of a drought. These impacts may, in fact, alter the way our system responds to the next drought.

“One region in California where drought impacts have been most concentrated is the Sacramento San Joaquin Delta. Drought impacts have been outsized here, not just because the Delta represents the convergence of waters originating over a watershed that constitutes a majority of the state’s landmass but also because of the Delta’s economic importance. Water pumped from the Delta supplies two-thirds of Californians and irrigates 45% of the fruits and vegetables produced in the US. Additionally, 80% of California’s commercial fish species rely on the Delta.

“Truly, the impacts of drought on the Delta have far-ranging repercussions, and success in figuring out how to promote resilience in the face of these steep challenges in the Delta can provide a valuable model for the rest of the state and beyond.

“Impacts of drought on the California Delta have led to new areas of investigation and management practices to address issues involving water quality, ecosystem-based management, public health, and more. Today, I have four experts working on investigating and addressing the many impacts caused by drought in the California Delta through research programs and management practices to build a more drought-tolerant Delta.

The panelists:

Dr. Shurti Khanna, Senior Scientist with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Dr. Shurti Khanna, Senior Scientist with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

“I am Shruti Khanna, and I work for the Department of Fish and Wildlife for the Bay-Delta region three, which includes the Bay and the Delta. While I was doing my Ph.D. in ecology at UC Davis, I worked in the Delta with remote sensing imagery, mapping invasive species that have spread in the Delta. I’ve been studying invasive species since 2004. I’ve also looked at how these species behave during droughts and how they affect the environment.

Dr. Michelle Leinfelder-Miles, Delta Crops Resource Management advisor with Cooperative Extension and the UC’s Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources

Dr. Michelle Leinfelder-Miles, Delta Crops Resource Management advisor with Cooperative Extension and the UC’s Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources

“I’m a cooperative extension advisor with UC’s Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources. Through partnerships with county governments, Cooperative Extension advisors are based throughout the state and develop research and extension programs to support local communities. As the Delta farm advisor, as I’m locally known, I am based in the San Joaquin County Cooperative Extension office and work on issues related to crop production practices and soil and water resource management throughout the Delta region. I have a bachelor’s from UC Davis in crop science and a Master’s and Ph.D. from Cornell in horticulture. And in addition to my educational and work background, I also grew up on a farm in San Joaquin County, so I’m back in my old stomping ground.

Dr. Josué Medellín-Azuara, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at UC Merced

Dr. Josué Medellín-Azuara, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at UC Merced

“I’m a member of the UC Merced faculty, and my research group works on water management issues and the climate extremes, including droughts and their economic effects on agriculture, communities, ecosystems. Through the years, I have conducted research in the Delta on various topics, including water use and water management for agricultural production and communities.”

Dr. Daniel Swain, a climate scientist with the Institute of Environment and Sustainability at UCLA

Dr. Daniel Swain, a climate scientist with the Institute of Environment and Sustainability at UCLA

“I’m a climate scientist, which seems like I take the top-down approach to things literally, thinking about climate change from an atmospheric perspective. Sometimes I like to say I’m a bit of a reformed meteorologist in the sense that I take a very weather-centric or episodic approach to climate change, really thinking about individual extreme events and the kinds of impacts they have on different systems. I got my Ph.D. at Stanford in earth system science; before that, I was at UC Davis for my atmospheric science degrees. So I’ve bounced around a bit of a triangle around the Delta over the years, geographically, although today I am speaking to you from Boulder, Colorado because my secondary affiliation is with the National Center for Atmospheric Research, which is located here.

QUESTION: What are some of the ways that drought impacts the Delta?

Dr. Daniel Swain

“When I’m talking about drought, I emphasize that drought is not an event that occurs really ever over a small area. You can have a flood that affects one watershed or an earthquake that affects one city, but droughts are almost always spatially and temporally broader than that. So usually, when there’s a drought in the Delta, there’s a drought throughout, most of California at a minimum, and often throughout much of the West.

“So it’s not just one watershed or a cohesive set of watersheds, but actually a whole broad region that has very different climates, geographies, and watershed characteristics, but often share the experience of drought simultaneously. That, of course, makes it more complicated to manage because it means you can’t just draw upon water in some immediately adjacent region where it’s abundant.

“So it’s not just one watershed or a cohesive set of watersheds, but actually a whole broad region that has very different climates, geographies, and watershed characteristics, but often share the experience of drought simultaneously. That, of course, makes it more complicated to manage because it means you can’t just draw upon water in some immediately adjacent region where it’s abundant.

“As a climate scientist, the other thing that I talk about in the drought context more and more is the role of temperature. Now, it’s obvious that to be in a drought, you need some degree of below average or low precipitation, so there needs to be less water falling from the sky, essentially. Historically, it used to be that some droughts were hot, some were cold, and some were in between. But these days, all the droughts we’re seeing are hot droughts.

“Increasingly, and somewhat surprisingly, the impact of that rising temperature is becoming outsized, relative to its historical contribution. Increasingly, we are seeing droughts whose severity are temperature-driven rather than precipitation-driven, per se. So the main reason we see more frequent and more intense droughts in places like California and the American Southwest is the direct effect of rising temperatures on evaporation, rather than large changes in the overall amount of precipitation. Other things are going on – we can talk about later with seasonality and intensity and frequency of storms. But really, it’s the temperature that’s driving some of the magnitudes of the droughts.

“Of course, the rising temperatures are also driving a lot of the ecological impacts, but in the Delta and California’s other ecosystems and watersheds, whether it’s through water temperature being too warm for fisheries, or because the landscape and the soil itself is drying out so much, it’s resulting in ecosystem shifts of the vegetation on land or drying of the vegetation that makes it more liable to burn at a high intensity in wildfires. And that’s affecting everything from wildfire severity to fisheries viability and everything in between. The Delta is at the geographic center of this and literally is aggregating the impacts to the west, the north, the east, and the south.”

Dr. Josué Medellín-Azuara

“I really like the way that Daniel [Swain] put drought in the Delta occurring in the context of what is happening elsewhere in the state, particularly in the Delta drainage basin. Upstream diversions and drainage, as well as exports, drive salinity and other conditions that feedback into farming and water treatment needs for communities and cities and flood management actions. So, despite the Delta having relatively firm water rights compared to other areas in the state, the droughts in the Delta in the water context occur more on the water quality side of things.

“So lower flows may occur concurrently with elevated salinity levels, and this may affect crop viability and increase treatment costs of water for cities and other places. This cascades at the end to the profitability of agriculture and the treatment costs and employment opportunities that might switch in some areas that are particularly more volatile in terms of salinity conditions. It might affect some of the decisions in the communities in terms of employment and activities, commuting, and other effects that compound with lower flows or changing water quality conditions in the Delta. So these are some of the things one might want to think about when we see so much change in flows and water quality to Delta.

Dr. Michelle Leinfelder-Miles

“Drought impacts agriculture in many ways. For example, the most obvious way is reduced water availability for irrigation and less soil moisture for crops to use, particularly tree and vine crops, between irrigation events. But drought affects agriculture in the Delta in some unique and perhaps less obvious ways.

“Essentially, there’s always water flowing through the Delta, so water quantity is not necessarily the issue during drought; rather, it is the water quality, particularly salinity, that impacts agriculture. Flows from the upper watershed push back ocean saltwater to protect water quality in the Delta, and for the Central Valley Project and State Water Project that deliver water to users south of the Delta.

“When flows are reduced, the salt and freshwater interface moves further inland and impacts the quality of irrigation water. The salinity of irrigation water can impact crop growth directly. Both the crop species itself and the crop stage of development may impart different degrees of salinity sensitivity or tolerance.

“Also, when irrigation water is applied to fields, salts are added to the soil. As a result, salts accumulate in the soil at higher concentrations than they existed in the applied water. And because soils are not homogeneous, salts may accumulate disproportionately depending on soil texture and layering. In other words, salinity may have fairly immediate outcomes on crop development, but the long-term impacts on soil quality are harder to quantify. One of my research interests is learning how to sustain or improve soil quality. And this includes investigating how surface water salinity impacts soil quality.

“I’ll wrap up by referring back to how water quantity is generally not a problem in the Delta. But back in 2015, Delta growers were involved in a voluntary curtailment program that restricted water diversions and a newer mandatory curtailment program is in place today. So both water quality and quantity can be impacts of drought for agriculture in the Delta.

Dr. Shruti Khanna

“The Delta is home to endangered species such as the Delta smelt, the longfin smelt, Chinook salmon, especially winter-run Chinook salmon, and it is a critical resting spot for many species of birds that migrate along the Pacific Flyway. In drought years, especially hot droughts, there can be stress to fish due to high temperatures, which can change their behavior and cause fish kills.

“Drought also leads to an increase in invasive aquatic species like submerged and floating plants, which change the Delta habitat in critical ways. They can cause low dissolved oxygen in the water, making it hard for the fish to breathe; they can slow down water and make it less turbid. Predators are able to hide in the vegetation mats. And while the clearer water makes it hard for Delta smelt and other endangered species to hide from their predators, the predators find it easy to hide in the vegetation mats.

“So what we have observed as over the past three decades, invasive species have significantly changed the habitat quality in the Delta and the increasing frequency of droughts and especially hot droughts, this can only get worse.”

Moderator: This question comes from Assemblyman Carlos Villapudua, who asks, how can California prepare for and mitigate the impacts of drought in the Delta to improve its resilience to disasters?

Dr. Shruti Khanna

“One thing that needs to happen is that during drought years especially, adaptive management of invasive species becomes very important, because there is a tendency for the species to increase during drought years, so they need to be more aggressively treated during those years.

“Then, due to the Eco Restore program and other programs, there is a lot of restoration right now going on in the Delta. It is important that these new restoration projects be designed to benefit native species over invasive species. Some of the ways that can be done are by actively planting native species, furthering the native species to come in rather than invasive species, and also by treating around the restoration site so that invasive species don’t enter the sites, giving the native species a chance to flourish. So those are some of the ways in which these effects can be mitigated.

RELATED:

Moderator Dr. Larsen: “We hear a lot about nature-based solutions as promoting resilience in California. And I think it’s important to note that we really need to put a lot of careful thought into how we deploy those nature-based solutions so that they themselves [can be resilient through extreme] events like drought. So I’ll pass it to Josué next to tell us more from his perspective on what California can do to prepare for and mitigate the impacts of drought.

Josué Medellín-Azuara

“Salinity might have some effects on water treatment and costs, and in also the viability of crops, particularly for some sensitive crops. So studies on the causal effects of salinity on crops can be useful to determine vulnerabilities on these sites. Some of that has been done, and it shows a high level of adaptability to saline conditions by farmers. So areas that are more volatile in terms of salinity levels see crops that are more tolerant. So a lot is already happening.

“But I would like to add the point of studying the distributional effects of drought on communities. How do changes in the economic activity due to droughts in some areas and the Delta affect the livelihood of people that live in these communities and the employment and income opportunities that come from it? So I can tell other areas how to [better balance things].

“As we know, crops and vegetation use the majority of the water that gets into the Delta, so having better information on the non-crop categories can be extremely helpful to identify policies that could help mitigate some of the effects on water quality and habitat for native species. So those are some of the areas I think could be helpful to pay attention to to be better prepared for the next drought.

Dr. Michelle Leinfelder-Miles

“One thing we can all do as Californians is recognize that drought is endemic to California by nature of our Mediterranean climate. We do experience drought every year because our summer months are dry. And it is only because of engineering and infrastructure that allows us to ignore that drought that occurs every year. So one thing we can all do, whether we’re managers, agency personnel, researchers, or simply water users, is plan and act like every year is a drought.

“One thing we can all do as Californians is recognize that drought is endemic to California by nature of our Mediterranean climate. We do experience drought every year because our summer months are dry. And it is only because of engineering and infrastructure that allows us to ignore that drought that occurs every year. So one thing we can all do, whether we’re managers, agency personnel, researchers, or simply water users, is plan and act like every year is a drought.

“But if I put my researcher’s hat on, I would say that having sustained funding for drought preparedness, including research, would be another way to prepare. For example, during the 2012 to 2016 drought, I was involved in research to investigate how surface water salinity impacts soil salinity, which coincidentally occurred during the drought. So often, funding is allocated retroactively, and opportunities to learn from critical opportunities can be lost.

“Furthermore, studies that span the extreme conditions like drought and flood provide these opportunities to understand systems, whether they’re agricultural systems or ecosystems. So to reiterate, California can prepare for and mitigate the impacts of drought by developing long-term and sustained strategies and funding to deal with it.

Question: How common is drought in the Delta, and how is the risk of drought predicted to change in the future due to climate change?

Dr. Daniel Swain

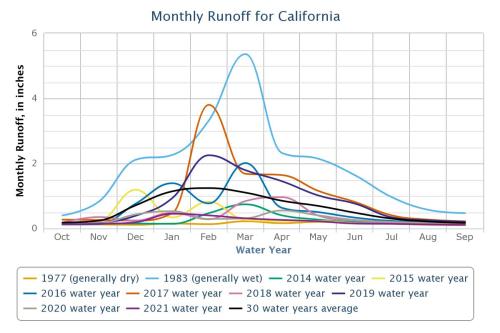

“Drought in the Delta is very strongly correlated with drought elsewhere in California, and California is no stranger to drought; it is an intrinsic part of the climate here. Depending on how you look at it, we get a drought every year during the dry season. It’s not a common thing to have a very, very dry season that coincides with the warm season; it is globally unusual. For anybody who’s from elsewhere or travels elsewhere on a regular basis, you might notice this; it’s pretty rare to have long, dry summers in a place that isn’t dry the whole year-round. Usually, the winter is the dry season.

“So in California, when the water is supplied by nature is exactly the opposite of when it is most needed in the human consumptive sense. And even in an environmental context, there’s an excess of water when it’s raining. Then the opposite is true in summer.

“But droughts, more traditionally defined as being years-long periods of unusually dry conditions, have already increased substantially due to climate change, mainly due to the warming temperatures themselves and the increased evaporative demand of the atmosphere. Essentially, the same amount of water falling from the sky as rain and snow just didn’t go as far as it used to – I don’t just mean that in terms of human consumptive sense. Even on the landscape, in places with no infrastructure and no water management, more of that water evaporates back into the atmosphere earlier in the year. Therefore, by the end of the dry season, there’s just less available in general.

“But droughts, more traditionally defined as being years-long periods of unusually dry conditions, have already increased substantially due to climate change, mainly due to the warming temperatures themselves and the increased evaporative demand of the atmosphere. Essentially, the same amount of water falling from the sky as rain and snow just didn’t go as far as it used to – I don’t just mean that in terms of human consumptive sense. Even on the landscape, in places with no infrastructure and no water management, more of that water evaporates back into the atmosphere earlier in the year. Therefore, by the end of the dry season, there’s just less available in general.

“Given what we see on the Colorado River and in California more broadly with climate change, how do we talk about drought and climate change era where the at least in California, the precipitation really hasn’t decreased much, but the intensity of droughts and the frequency of droughts has increased considerably already and is expected to further increase with each additional increment of warming.

“Some folks have started to call this aridification of the landscape because the overall state of dryness is moving in one direction only. The idea of a drought is that eventually, you emerge from drought and at least temporarily return entirely to the situation you’re in before the drought began. Increasingly, we do not see that; we are seeing droughts that are broken by increasingly extreme precipitation or interrupted by extreme precipitation as we got a taste of this past October, where we had the wettest day in Sacramento and parts of Northern California history in the middle of the singularly longest dry spell in history in the same places.

“Fortunately, that produced more benefits than harm in this particular context, because it’s been so dry, the rivers were so low that there wasn’t severe flooding as a result of it; it just kind of got absorbed by the landscape for the most part and generated some beneficial runoff. But I think the tricky part is looking forward to the future; we can’t just think about drought in isolation. There’s actually a lot of evidence that the variability of California’s hydroclimate is already starting to increase, but especially will increase in the next few decades with an additional half a degree or degree of global warming over the next few decades.

“That variability is likely to continue to increase, and that includes on the wet side. One of the things that we’re trying to emphasize as we talk about drought is the rapidly escalating risk of very large flood events at the same time as increasingly severe droughts. So even if the landscape is aridifying overall, mainly due to rising temperatures and not so much due to decreasing precipitation, we still expect those increasingly long and intense dry spells to be interrupted by increasingly intense storm events or storm sequences that can produce the opposite problem.

“Then that begs the question, is there a way to co-manage these events in a way that actually helps reduce the harms from both of the events going on? One of the promising approaches here that’s what we think the physical climate will look like in California’s future is essentially leveraging the floods that we do have to periodically and sporadically to recharge our aquifers. The state of California calls this Flood MAR or flood managed aquifer recharge. The idea is, you take the windows of opportunity when there are very large excess flows that you don’t know what to do with, or if you don’t do something with it, it’s going to flood places you don’t want to flood, and try and move them to places that you’ve pre-designated as recharge zones or recharge basins. So thereby recharging groundwater, improving resilience against the next drought, while ideally reducing flood risk in the moment to the places you really don’t want to flood, which is mostly the populated urban areas.

“That, of course, is easier said than done for a variety of reasons that relate both to physical infrastructure and policy. But, that’s the kind of intervention that I think is increasingly being talked about that is, in my view as a physical scientist, is consistent with the kind of future we’re already starting to move toward and that we’re really going to start to experience to an even greater degree over the next few decades.

Moderator: The other side of the coin is managing demand. And that is a nice segue into our next question: How can we reduce the human water demand?

Dr. Josué Medellín-Azuara

“We have warmer droughts, and with warmer droughts in many places, there could be a higher evaporative demand in crops. So there’s a component of drought that taxes how much water we have to put into crops. So, there might be an increasing amount of water needed for irrigation during droughts.

“As these become more frequent in the future, from a water balance perspective, we need Delta outflows to keep salinity controls for agriculture, cities, and communities. On the other hand, we need increased applied water in the Delta drainage basins that use a lot of the water that goes back into the Delta. We should think about reductions in consumptive use as the water lost to the atmosphere does not go back to the system – at least immediately or directly. It goes into those atmospheric rivers and other things.

“In terms of reducing consumptive use, cities have done a lot, and agriculture has also done its part in increasing application efficiency. But at the end of the day, we cannot make more water, so we have to cut back a little bit into this consumptive use that occurs by decreasing these losses that are not going back to the system, such as reducing irrigated areas. This is especially true for places with overdrafted basins such as the San Joaquin Valley and in other areas such as coastal areas. So that might be one of the strategies that we can use to reduce human use.

“Also, reduction of irrigation of other areas, such as 40 to 50% of the urban uses in irrigation of our landscapes, depending on the location. Those are some opportunity areas we might want to look into to reduce demand.

Dr. Michelle Leinfelder-Miles

“It’s pretty clear to Californians that agriculture is a big user of water in California. And the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act will have a heavy role in reducing agricultural acreage in California, especially in overdrafted areas. I wouldn’t say that we’ll see a big change in the agricultural area in the Delta because the hydrology in the Delta is different, where groundwater is in shallow layers of the soil, unlike the San Joaquin Valley, where it keeps falling lower and lower in the soil profile.

“But overall, in agriculture, there are many practices that we’re researching and that growers are employing to try to manage how much water is being used in crops. Those include irrigation methods, including drip irrigation and other forms of micro-irrigation, and also looking at drought tolerant crops, specifically drought-tolerant varieties of crops. So I have colleagues who are not only looking at crop species but varieties within species that may be able to tolerate higher levels of drought or higher levels of salinity.

Dr. Larsen: What is the landowner’s willingness to adopt these changes in practice and the extent to which you’ve been engaging with Delta landowners in this research on drought-resilient agriculture?

Dr. Michelle Leinfelder-Miles

“I think that there’s certainly a willingness because the writing’s on the wall. Drought is at least cyclical, if not endemic, and growers are well aware of that. These reduced irrigation or deficit irrigation practices are widespread in the agriculture community, both in the Delta and outside the Delta. Many of these practices have become recognized for improving yield or improving crop quality, such as drip irrigation in crops like processing tomatoes or wine grapes. So those things make it very easy for growers to see the data and implement the practices.

“I think that there’s certainly a willingness because the writing’s on the wall. Drought is at least cyclical, if not endemic, and growers are well aware of that. These reduced irrigation or deficit irrigation practices are widespread in the agriculture community, both in the Delta and outside the Delta. Many of these practices have become recognized for improving yield or improving crop quality, such as drip irrigation in crops like processing tomatoes or wine grapes. So those things make it very easy for growers to see the data and implement the practices.

“In terms of the other crop or species tolerances, I think growers will be on board once we have a little bit more scientific understanding. These sorts of things will take regional studies that look at not only the species are these varieties in a certain location where they might be developed, but also taking those studies a little bit broader and investigating them, both in the Delta environment and in other environments throughout the state.”

Dr. Larsen: “For the sake of completeness, I will add that there’s also a lot that urban water users can do to reduce demand. I know that as a resident of the city of Sacramento, there have been some monetary incentives to decrease the grass coverage on individual yards. Grass is very water-hungry. Other cities like San Diego have made big strides in reducing urban water demand. So I think this is all quite promising.

QUESTION: Our next question comes from Judith Drexler at the USGS. She asks, recent research suggests that atmospheric rivers will increase in the future under climate change, yet total precipitation is unlikely to increase. How will this increase in the episodic delivery of precipitation affect ecosystems, agriculture, and communities?

Dr. Shruti Khanna

“The problem is that when you have a heavy flood during a drought, it doesn’t necessarily bring about advantages that it could have – at least for ecosystems. For groundwater recharge, it might work well. But part of droughts, especially when flooding happens during a hot period, salmon, which usually love floods and love the Yolo bypass to be flooded, get nice and fat in there – they do not do that when the droughts are hot, and the water is hot. So it doesn’t benefit fish as much. So that is one issue.

“The other thing that happens, evident from our recent biggest atmospheric river that went through is there was a fish kill in Putah Creek. So sometimes, when the land is so dry, it can mobilize contaminants in the soil, and the floods bring that along, and it can actually cause more harm to fish.”

“For invasive species, generally high flows will flush out invasive species; the water gets a little freer of aquatic species. But, on the other hand, it is also an excellent dispersal mechanism. So it spreads out the species by flowing them out of flooded islands and places where water tends to collect. Then when the next year, the flows are lower, those species already have propagules in there and can spread out again. So overall is for ecosystems, this is harder on them than an actual increase in precipitation and colder floods would be.”

Dr. Michelle Leinfelder-Miles

“This sort of episodic precipitation or these changes in precipitation over time, particularly in the Delta, will be manifest through the changes in salinity that we see from saltwater intrusion. We see a temporal change in salinity in the Delta, just due to the tides. But when it comes to low precipitation and flows, we see the salinity move further inland. And I think that will, in the short term, manifest as changes in crop yield or quality. In the long term, it may have an impact on what crops are planted in the Delta or what lands can be used for agriculture. I think the question would have different answers in different parts of California. But in terms of Delta agriculture, those would be the impacts that I would envision.

Dr. Josué Medellín-Azuara

“One way of seeing this is we have warmer droughts, where we might see more precipitation, but it won’t be in the form of the snow. So this opportunity to bring floodwater in wet years into groundwater storage can make up for this loss of various surface water reserves in the Sierras for the summer irrigation and other water needs. So, seizing the opportunity to store water on the ground is a good avenue, and some rapid guidelines for that occurring are needed.

QUESTION related to the increasingly episodic nature of these precipitation events that we’re seeing in California. Do the high precipitation events mentioned by Dr. Swain reverse the increased soil salinization caused by the drought?

Dr. Michelle Leinfelder-Miles

“Unfortunately, we can’t say that with certainty, but we can probably make some assumptions about that. Certainly, we rely on rainwater to help us leach salts out of the soil profile. But due to the hydrology of the Delta, particularly the shallow groundwater, sometimes we find that to be a barrier that prevents leaching of salts out of the root zone. So we may have a lot of rainfall that comes down, as in the 2016-2017 rainfall year that followed the drought, we did see soil salinization increase during those drought years in certain studies that I was involved in. Unfortunately, the study didn’t go into the next year due to funding and other constraints. So we would hope that and assume that the soil would get cleaned out to some extent of those salts that had built up, but due to these hydrology issues, and also just the heterogeneous nature of soils, where soil layering or soil texture differences may hinder leaching of it. So I don’t have a very conclusive answer. It’s probably yes and no.

Dr. Larsen: “I would say, from my perspective, the management of salinity in the Delta is one of, if not the biggest challenge in managing the suite of conditions that we experienced during drought. Michelle and I are both engaged in planning a series of workshops to look to the next big drought or extended drought conditions in California, to develop a very forward-thinking strategy for how we manage salinity, and assess the impacts of those management strategies on a whole host of sectors, including agriculture. This issue of soil salinization is one of the big uncertainties that keep coming up in the planning discussions.

QUESTION: How will sea level rise impact the Delta during drought conditions?

Dr. Daniel Swain

“Sea level rise is interesting when it comes to the Delta for a couple of reasons. First of all, Some folks may even forget that the Delta is directly connected to the ocean, so if the sea level rises, the water level in the Delta will rise essentially by the same amount, the tidal cycle notwithstanding. The Delta is already very low lying and absent levees, much of it is below sea level or would be below sea level. So you have this place that is connected to the ocean that is below sea level that could result in some problems when the ocean level rises, which it is – ocean level has already risen, but it’s doing so in a very spatially heterogeneous way globally.

“Sea level rise is actually very different from one place to another. You might think that a rising sea raises all ships evenly; it does not. And not only does it vary in space; it also varies in time. So we have higher sea levels when the North Pacific Ocean is particularly warm. So there are variations with La Nina and El Nino events; for example, there are decadal oscillations, but overall, the ocean levels are obviously rising because of climate change, partly because of just the thermal expansion of water.

“Primarily, as we move to the next few decades until the middle part of the 21st century, it will be due to melting ice sheets which is accelerating, and that’s a nonlinear process. The challenge is that we don’t know how much it will accelerate further. So sea level rise today is already faster than it was a decade or so ago and is likely to be faster a decade or so from now.

“The tricky part is because while we often talk about median estimates for how much the ocean levels likely to rise, those estimates are very asymmetric – at least the uncertainty in those estimates is asymmetric. So it’s not like we’re equally uncertain that sea level rise could be lower than expected or higher than expected; there’s almost a 0% chance that sea level rise will be less than expected. And there’s a pretty reasonable chance it could be significantly higher than expected. So the uncertainty with respect to sea level rise is very asymmetric about the median, meaning that the upper tail, the extreme sea level rise outcomes are much more likely than the very low sea level rise outcomes.”

“So, how do you plan for that? This is, of course, a problem anywhere along the coastline globally. But in the Delta, that’s especially challenging because we do have the system that’s critical for the environment, agriculture, and the transport of freshwater through the state. So how do you deal with uncertainty when you know that the very worst outcomes are more likely than the very best outcomes? But we can’t really put a number on it since that’s actually one of the biggest challenges. And I don’t have any good answers for that other than to really emphasize that the upper end of the outcomes are potentially a lot higher than the median.”

Josué Medellín-Azuara

“One of the concerns is flood management; the hydraulic pressure rises on the levees that are around many of the areas in the Delta. And also, the pushback of the salinity line in the Delta to protect water quality for in-Delta water users and Delta exports. So again, we need to be really prepared for how that is looking in the future, which looks like the upper end is more likely. So that is an area on which you focus your efforts.

Dr. Shruti Khanna

“Another thing about sea level rise, especially if it’s towards the upper end, is it is likely to increase the pressure on existing levees, which increases the chances of levee breeches in the Delta, and then because the Delta is so subsided, that increases the chances of quick filling up of the bowl with saline water, which can lead to very severe impacts that might take years to then flush out. So there are definitely more risks associated with sea level rise depending on where it lands.”

Dr. Laurel Larsen: One of the ongoing efforts in the Delta to mitigate that particular challenge is wetlands are being created and designed specifically for subsidence reversal. Wetlands are incredibly effective at helping to fill in that bowl through natural processes. And so, continuing to invest in wetland restoration is one of those things that could help promote resilience to these challenges.

Wrap-up question to the panel: What are some of the biggest knowledge gaps that still need to be addressed?

Dr. Michelle Leinfelder-Miles

For me, I think that understanding how surface water salinity impacts soil salinity and the long-term impact of soil salinity on agriculture viability is a lingering question where we need to do some more work.

Dr. Shruti Khanna

“A couple of things that are very important to consider is how can we create temperature refuges for our fish communities so that they can survive what is clearly coming in the future. And then also, a lot of habitat modeling needs to happen with regards to invasive aquatic species so that we can predict and manage the risk of the spread of these species so that we can keep the habitat more conducive to our native species.

Dr. Josué Medellín-Azuara

“Water balances, I think; it’s always my all-time favorite. I think just quantifying what water use of crops, floating vegetation on open water, and with a more extreme climate. So these are some areas in which we could put in some effort.

Dr. Daniel Swain

“One of the biggest uncertainties with climate change is there are, of course, climate model uncertainties, climate science uncertainties; we don’t know exactly how much precipitation may change or exactly how much it may warm. But really, one of the things that dominates is uncertainty about how much the globe, the whole planet as a whole, is going to warm. And that’s not a scientific uncertainty; primarily, that’s a question about local policy and global carbon emissions. And the reality is the Delta and the rest of California will experience an amount of climate change that is largely dictated by what happens in other countries around the world.

“California, of course, can be a leader in mitigating climate change. But ultimately, it’s still going to experience that same amount of climate change if the rest of the world doesn’t also follow suit. So it’s sort of a regional and local manifestation of a global challenge. So one of the greatest uncertainties is what we do globally; how much more carbon do we emit? And how much more global warming is there? How much more will the Delta change from a climatic perspective moving forward? So that’s something we don’t know. On the other hand, it’s something that we have control over collectively. And that’s one of the most important things to remember is that this is a challenge. That is not a foregone conclusion. We don’t know how much it’s going to warm because we can make decisions that cause it to warm a lot less than other decisions. And so I think I’ll leave it at that.”

2021_DroughtSyndrome_OnePager-CCST