El Niño and La Niña are complex weather phenomena resulting from ocean temperature fluctuations in the Equatorial Pacific.

Higher-than-normal sea-surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean characterize El Niño. During this phase, the trade winds weaken, causing warm water to move eastward toward the West Coast. In contrast, La Niña involves cooling sea-surface temperatures in the east-central equatorial Pacific. La Niña events are marked by stronger-than-normal trade winds that drive warm water toward Asia. These variations lead to significant global weather impacts.

El Niño and La Niña episodes generally last from nine to 12 months, though they can occasionally persist for several years. These events typically occur every two to seven years, but they don’t occur on a regular schedule. Generally, El Niño tends to happen more often than La Niña. As opposing phases of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), they cannot occur at the same time, and there are many periods when neither is present.

What is ENSO?

The El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a term used to describe the variations in the equatorial Pacific’s ocean surface temperatures and air pressure.

When sea-surface temperatures rise above average by about 1 degree Fahrenheit or more, El Niño can develop. Conversely, when temperatures dip below average, La Niña may develop. In ENSO-neutral conditions, temperatures hover around average, preventing the formation of either phenomenon.

The air pressure component involves comparing pressure differences between the western and eastern equatorial Pacific. Readings are taken from Darwin, on Australia’s north-central coast, and Tahiti, over 5,000 miles to the east. Lower-than-normal pressure in Tahiti and higher-than-normal pressure in Darwin favor El Niño development, while the reverse supports La Niña.

Both temperature and air pressure conditions must align for either El Niño or La Niña to occur.

How do El Niño and La Niña impact the weather?

El Niño and La Niña have minimal impact on summer climate in the United States; the most substantial influence occurs in winter.

During El Niño events, the jet stream typically moves southward, leading to rainier and cooler weather across much of the Southern US while bringing warmer conditions to the Northern US. Globally, El Niño can result in warm, dry weather in regions such as Asia, Australia, and India, and influence weather patterns in parts of Africa and South America. El Niño impacts marine life by disrupting the upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich water along the Pacific coast, leading to a decline in phytoplankton and affecting the entire marine food chain.

With La Niña, the jet stream shifts northward, leading to warm and dry conditions in the Southern US and cooler, wetter weather in parts of the Northern US, especially the Pacific Northwest. La Niña can also lead to a more severe hurricane season. Globally, parts of Australia and Asia can be wetter than usual. During La Niña, the Pacific coast experiences colder, nutrient-rich waters, which support increased marine life and draw more cold-water species to regions like the California coast.

How does El Nino & La Nina affect California?

During El Niño, California often experiences wetter and cooler conditions, which can lead to increased rainfall and potential flooding. These heavy rains can contribute to mudslides and affect agriculture by both replenishing water supplies and causing crop damage.

Conversely, La Niña tends to bring drier and warmer conditions, exacerbating droughts and increasing the risk of wildfires. The lack of precipitation during La Niña can strain water resources, impacting both agricultural production and urban water supply.

In Northern California, there is little correlation between precipitation and most ENSO patterns, according to the National Weather Service. They note that Southern California is generally much more impacted with El Nino conditions bringing higher than normal precipitation and La Nina bringing below normal precipitation to Southern California.

So there are no guarantees. Not every El Niño period is extra wet in the Golden State, and not every La Nina means a dry year. However, between 50 and 70 percent of El Niños since 1950 have led to above-average winter precipitation in California, according to the National Weather Service, which gives a slight edge to wet El Nino years.

Coverage of El Niño and La Niña on Maven ‘s Notebook

NIDIS: The El Niño-Southern Oscillation and drought outlook in the United States

By Andrew Hoell, NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory The El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a recurring phenomenon defined by shifts in tropical Pacific Ocean sea surface temperatures, ocean currents, and overlying atmospheric winds. It manifests in three distinct phases: neutral, La Niña, and El Niño. In the contiguous United States, La Niña generally leads to below-average precipitation and above-average temperatures in the Southern U.S. and the opposite in the Northern U.S. during cool seasons. Conversely, El Niño typically causes above-average precipitation and […]

EOS: Tree rings record history of jet stream-related climate extremes

Persistent spatial patterns of summer weather extremes in the northern hemisphere recorded in tree ring growth records provide a thousand-year history of jet stream ‘wave5’ dynamics. by Susan Trumbore The degree to which global warming will affect atmospheric dynamics and, therefore, extreme weather is still uncertain. Broadman et al. [2025] find a clever way to reconstruct the history of one dynamical pattern that occurs when the jet stream forms five peaks and troughs around the Northern Hemisphere (referred to as […]

YALE CLIMATE CONNECTIONS: Why winter rains keep skipping the Southwest

by Bob Henson, Yale Climate Connections Climate change appears to have driven an ongoing 25-year shortfall in winter rains and mountain snows across the U.S. Southwest, worsening a regional water crisis that’s also related to hotter temperatures and growing demand. Multiple studies now suggest that human-caused climate change is boosting an atmospheric pattern in the North Pacific that favors unusually low winter precipitation across the Southwest. This weather pattern – known to scientists as a negative mode of the Pacific […]

USGS: Long-term satellite data reveal how climate shapes West Coast shorelines

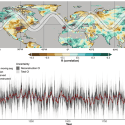

By the USGS Coastal and Marine Hazards and Resources Program New research uses decades of satellite data to show how climate variability—particularly El Niño and La Niña cycles—drives shoreline change along the North American West Coast. The research, led by the Université de Toulouse and partners, highlights how coastal erosion and shoreline movement vary significantly with time and with latitude. By analyzing waterline positions—where land meets ocean—between 1997 and 2022, scientists found that in the Pacific Northwest, seasonal waterline […]

The growing impact of ENSO on extreme drought and flood events

By NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic & Meteorological Laboratory Extreme hydroclimate events, such as droughts, floods, and heavy rainfall, account for a substantial portion of weather-related disasters in the United States, leading to significant socio-economic losses involving agriculture, water resources, and public health, among others. For instance, from 1980 to 2024, droughts were responsible for approximately $368 billion in economic losses for the United States, while inland flooding was responsible for $293 billion in damages. In a new study published in Climate […]

Read all coverage on Maven’s Notebook.