Last year, the Supreme Court ruled that the Clean Water Act didn’t apply to ephemeral streams. According to a new study, that’s more than half all the fresh water in the U.S.

By Hillel Aron

![]() Last year, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the 1972 Clean Water Act should only apply to waters that are navigable year-round, and not to ephemeral streams — waterways that are underground for much of the year, until there is significant rainfall.

Last year, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the 1972 Clean Water Act should only apply to waters that are navigable year-round, and not to ephemeral streams — waterways that are underground for much of the year, until there is significant rainfall.

In doing so, the court significantly rolled back federal environmental protections that had been around for half a century.

A new study seeks, for the first time, to quantify the volume of water that was affected by last year’s ruling. According to the paper, published Thursday in the journal Science, ephemeral streams are responsible for roughly 55% of all water that comes from regional river systems in the U.S. In other words, more than half of the water flowing in and out of rivers in the U.S. is no longer under the protection of federal law.

This newly opened loophole in the Clean Water Act could have massive implications, the study’s authors say. Waterways are, after all, connected, and pollutants from one stream inevitably make their way downstream.

“If these ephemeral streams are no longer regulated under the Clean Water Act, this is a potential pathway for nutrients and pollutants to get into downstream water bodies that are still nominally regulated,” said the paper’s lead author, Craig Brinkerhoff, a postdoctoral researcher at Yale School of the Environment.

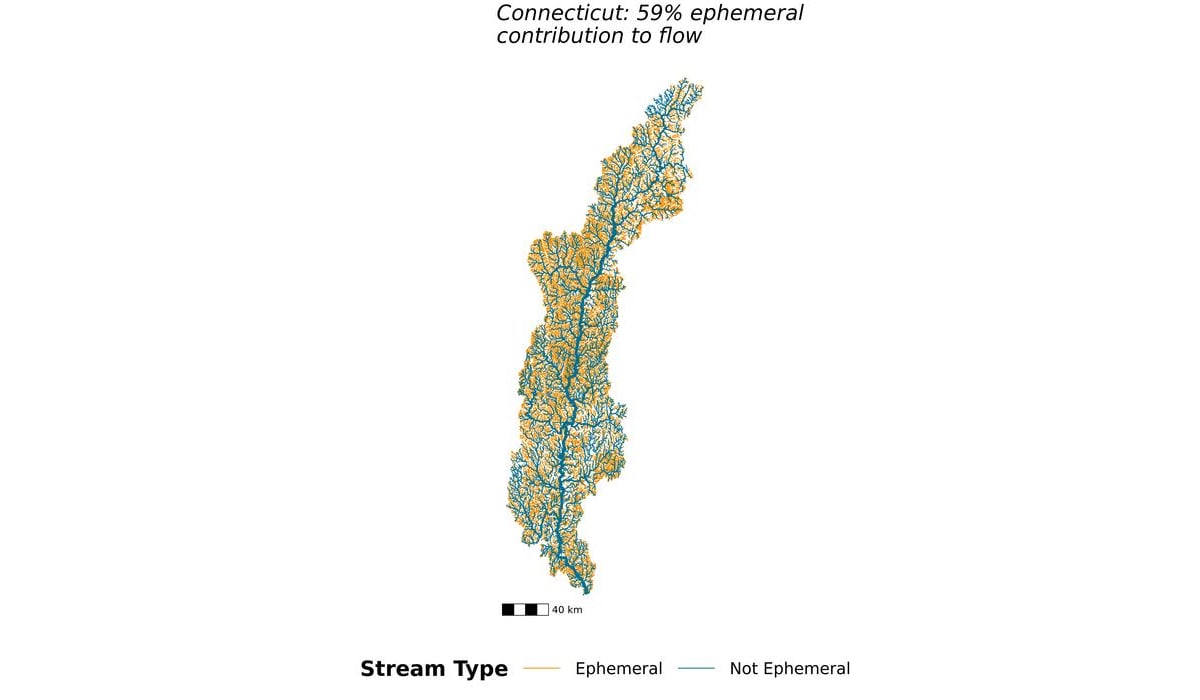

Take, for example, the Connecticut River, the longest river in New England, flowing 406 miles through four different states. The main part of the Connecticut is perennial — it flows year round. But it is fed by, and feeds, dozens of tributaries and countless tiny streams, some of which are underground much of the year. The full weight of the Clean Water Act no longer protects those streams, which often look like dry gullies, despite the fact that any pollution there will eventually find its way into the Connecticut.

According to the study, 59% of Connecticut’s watershed is comprised of ephemeral streams. Rivers in the Western United States are even more affected by the ruling. In the Black Rock Desert watershed, 94% of the water is underground for much of the year.

Some states, like California, have their own protections. But many do not, and have relied on federal law, which gives third parties the right to sue for polluting waterways. Much of the enforcement of the Clean Water Act is done by nonprofits like the Waterkeeper Alliance and Riverkeeper suing polluters. Now, it will be left up to the states to regulate ephemeral streams.

“The vast majority of states have been depending on the national permit system to control water pollution,” said Doug Kysar, a Yale Law professor who also worked on the project with Brinkerhoff. To force states to take over that regulation is not only a big shift, it’s a fundamentally unfair arrangement.

“Upstream states don’t necessarily want to be saddled with the cost of pollution control, if the benefits go to downstream states,” Kysar added. “Every year in the summer, there’s a huge dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico that’s caused by pollution runoff. It’s an area the size of a state where nothing lives. A lot of that comes from pollution runoff, from states like Nebraska and Indiana. But it affects fishermen in Louisiana.”

Kyser said there should be national-level controls on water pollution.

“The Supreme Court is now rolling us back to the dynamic that didn’t’ work for 150 years,” he said.