In 2014, California passed the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (or SGMA), requiring local agencies to be formed and groundwater sustainability plans to be written for all groundwater basins subject to SGMA. Those plans must avoid six undesirable results, one of which is “significant and unreasonable” impacts to groundwater quality.

Ensuring that groundwater quality is maintained at a standard that is acceptable for its intended uses, such as drinking water, is particularly important as impacts to groundwater quality can affect a variety of users but tend to hurt small water supply systems and domestic well owners disproportionately. Therefore, writing plans that protect drinking water and ensure the management actions required under the law do not negatively impact groundwater quality will be critical and requires understanding a host of existing federal, state, and local regulations and laws related to water quality.

In general, the US Environmental Protection Agency sets the baseline, the overarching rules, and minimum standards for all states; states then have the opportunity and the right to further regulate above and beyond what the federal regulation provides. Similarly, at the local level, there are opportunities for more detailed regulations. So when considering water quality, there are three levels of water quality regulations: federal, state, and county levels.

This post is a primer on water quality regulations with a focus on groundwater quality regulation. It is based on a lecture from Dr. Thomas Harter’s Groundwater Shortcourse held earlier this year, as well as the textbook, Watersheds, Groundwater and Drinking Water, and some internet research.

Federal water quality regulation

Prior to the early 1970s, there was little regulatory oversight over water-polluting activities and few legal means available to redress impacts to water quality or prevent such impacts from occurring. The only legal defense was through common law, primarily tort law. However, by 1970, common law was widely recognized as being inadequate to deal with increasingly complex pollution issues resulting in the passage of several landmark pieces of legislation in the 1970s that established a regulatory framework and created the US Environmental Protection Agency.

National Environmental Policy Act or NEPA

The National Environmental Policy Act was one of the first laws that established the broad national framework for protecting the environment. The basic policy of NEPA is to assure that all branches of government give proper consideration to the environment prior to undertaking any major federal action that significantly affects the environment.

NEPA requires federal agencies to assess the environmental effects of their proposed actions prior to making decisions. The range of actions covered by NEPA is broad and includes actions such as permit applications, adopting federal land management actions, and constructing highways and other publicly-owned facilities. Agencies must evaluate the environmental, social, and economic effects of their proposed actions and prepare an environmental impact statement or an environmental assessment. There are opportunities for public review and comment on the environmental documents.

Click here to learn more about the National Environmental Policy Act.

Clean Water Act

The Clean Water Act protects surface water resources from pollution through permitting, regulating, and incentivizing pollution control at the source. The Act created the nation’s first surface water pollution prevention program.

The Clean Water Act framework includes:

-

- The National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (or NPDES) which controls all municipal and industrial discharges into waterways through a permit system.

- Technology-based minimum effluent standards for numerous industries

- Standards for protecting ambient water quality (Ambient water quality refers to open waters such as rivers, lakes, and streams, as opposed to closed water supply systems that distribute treated water or wastewater.) The standards went largely unused in the early years but are now used as a regulatory tool for controlling point and nonpoint source pollution by using the requirement that surface waters cannot exceed the Total Maximum Daily Load (or TMDL) for covered pollutants in surface waters.

- Specific provisions for spills and other accidental discharges of toxic chemicals

- Funding support for public water treatment works (as few existed prior to the 1970s)

- Assessment and planning guidelines for nonpoint source pollution prevention

- A permit system for discharging dredged and fill materials into waters of the United States, including wetlands

The Clean Water Act focuses on protecting surface water; however the ability to protect groundwater under the nonpoint source and TMDL program is weak as it really only applies when groundwater seeping is into a river or stream and is impacting surface water quality.

Click here for more information on the Clean Water Act.

Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act

Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act of 1972 (MPRSA) or Ocean Dumping Act regulates intentional ocean disposal of materials, authorize any related research, and provides for the designation and regulation of marine sanctuaries.

Click here to learn more about the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act.

Safe Drinking Water Act

The Safe Drinking Water Act sets national standards for drinking water quality. Because groundwater accounts for about half of the nation’s drinking water supply, it was the first federal regulation to address groundwater protection. The Act also established a permit system for underground injection and special protections for aquifers that are the sole source of drinking water in a region.

The Safe Drinking Water Act sets national standards for drinking water quality. Because groundwater accounts for about half of the nation’s drinking water supply, it was the first federal regulation to address groundwater protection. The Act also established a permit system for underground injection and special protections for aquifers that are the sole source of drinking water in a region.

Guidelines were established for the assessment and protection of the sources of drinking water. For groundwater, this is the wellhead protection area; for surface water, it is the watershed upstream of the drinking water intake. In California, the surface water source assessment program and the wellhead protection area program have been combined into a single Drinking Water Source Assessment Program.

The Safe Drinking Water Act regulates the contaminant levels in drinking water by setting Maximum Contaminant Levels that need to be observed in public water supply systems. A public water supply system is any water system (public or private) with 15 or more connections serving 20 or more people for more than 6 months. Small public water systems are systems with 5 to 14 connections and are also regulated by state or by local agencies under the Safe Drinking Water Act.

The Safe Drinking Water Act does not apply to privately owned domestic wells, and does not (nor was intended to) address sources of contamination.

For more information on the Safe Drinking Water Act, click here.

Federal legislation addressing pollutants

The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act or FIFRA

The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act specifically addresses pesticides and similar substances by establishing standards for permitting their use. A new pesticide needs to be reviewed, tested in the field, and in the lab; there are certain standards it must meet to be allowed to be sold. It must come with a particular label that prescribes when and where and how much can be applied.

Click here to learn more about the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act.

The Toxic Substances Control Act

The Toxic Substances Control is a broader regulation. There are hundreds of thousands of toxic substances out there with hundreds more coming on the market each month as they are developed for specific industrial or consumer purposes. The Toxic Substances Control Act regulates the management of these substances, the disposal of these substances, and also incentivizes better practices on these substances.

Click here to learn more about the Toxic Substances Control Act.

Resource Conservation and Recovery Act

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act is the primary regulatory tool created to control discharges of pollutants into surface water or onto land, thereby preventing groundwater pollution. RCRA regulates the use of underground storage tanks, a common source of industrial groundwater contamination. It also addresses landfill and landfill permits, waste disposal permits, and the ‘cradle to grave’ control of hazardous wastes.

Click here to learn more about the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act.

Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act or CERCLA

The Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act is commonly known as the Superfund Act. The Act addresses pollution and specifically groundwater pollution, that has already occurred. Superfund sets up a federal fund, often with a state fund counterpart, so cleanup can begin before the responsible parties are determined. Once identified, responsible parties then repay the money back to the fund. “The wrangling over who are the primary responsible parties on these sites is no small part of that,” noted Dr. Harter.

Who implements the federal regulations?

At the federal level, all of the regulatory frameworks are managed by the US Environmental Protection Agency. State agencies are given the option to implement these acts on behalf of the US EPA. The intent of the federal legislation is to establish minimum standards that apply to all the states to avoid duplicative efforts. States are free to establish stricter regulations than those mandated by federal guidelines.

In California, the Clean Water Act is managed by the State Water Resources Control Board. California passed its own clean water legislation, the Porter-Cologne Act in 1969, preceding the federal Clean Water Act by three years. The Porter-Cologne Act was essentially the beginning of today’s State Water Resources Control Board. Up until 1969, the Board was only dealing with water rights but through the legislation, the implementation and the regulatory control for the Porter-Cologne Act was given to the State Water Board, and as part of that, nine regional water boards were also established.

In California, the Clean Water Act is managed by the State Water Resources Control Board. California passed its own clean water legislation, the Porter-Cologne Act in 1969, preceding the federal Clean Water Act by three years. The Porter-Cologne Act was essentially the beginning of today’s State Water Resources Control Board. Up until 1969, the Board was only dealing with water rights but through the legislation, the implementation and the regulatory control for the Porter-Cologne Act was given to the State Water Board, and as part of that, nine regional water boards were also established.

The Safe Drinking Water Act is managed in California by the Division of Drinking Water, which is used to be under the Department of Public Health, but was moved to the State Water Resources Control Board several years ago.

The Department of Pesticide Regulations regulates all aspects of pesticide sales and use, including the FIFRA guidelines. The Department has implemented a groundwater protection program that primarily addresses applications and management of pesticide use on the farm.

Implementation of the Toxic Substances Control Act resides with the Department of Toxic Substances Control, and to some degree with the regional water boards. The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act permits reside with the regional water quality control boards.

So in California, it is primarily regional water boards in the nine regions implementing regulations related to water quality.

State water quality policies and regulations

Porter Cologne Act

The most significant state legislation pertaining to water quality is the Porter Cologne Act, which was adopted in 1969, three years prior to the federal Clean Water Act.

The Porter-Cologne Act was named for the late Los Angeles Assemblyman Carly V. Porter and then-Senator Gordon Cologne and was recognized as one of the nation’s strongest pieces of anti-pollution legislation. The new state law was so influential that Congressional authors used sections of Porter-Cologne as the basis of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, more commonly known as the Clean Water Act. (State Water Board website)

The Act applies to surface waters, wetlands, and groundwater and to both point and nonpoint sources of pollution, expressly stating that the all the waters of the State are to be protected and that the activities and factors affecting the quality of water ‘shall be regulated to attain the highest water quality within reason’ and the state must protect the quality of water in the State from degradation.

The Act established the nine regional water boards who oversee water quality on a local and regional level. One of the most important provisions is that the regional water boards must prepare and periodically update basin plans, which define beneficial uses, establish water quality standards to protect those uses, and adopt an implementation plan.

Porter Cologne provides several options for enforcement, including cease and desist orders, cleanup and abatement orders, administrative civil liability orders, civil court actions, and criminal prosecutions.

Click here to learn more about the Porter-Cologne Act.

Anti-degradation policy

In 1968, the State Water Resources Control Board adopted an antidegradation policy (Resolution 68-16) that applies to high-quality surface water and to high-quality groundwater.

In 1968, the State Water Resources Control Board adopted an antidegradation policy (Resolution 68-16) that applies to high-quality surface water and to high-quality groundwater.

“It requires the high quality be maintained to the maximum extent possible,” said Dr. Harter. “There are specific exceptions to when that high-quality water can be lowered because of discharges. If there is change, it needs to be consistent with the maximum benefit to people of California and it cannot unreasonably affect beneficial uses of water; those beneficial uses include drinking water, recreational uses, irrigation water, stock water, and industrial uses.”

“So it cannot unreasonably affect beneficial uses of water, and it cannot result in water quality that is actually lower than existing standards,” he continued. “That last point seems intuitive but it’s important to actually make that distinction. What the antidegradation policy says even if the water quality is well above the standard, we want to preserve that high quality; we don’t want it to get worse.”

He noted that there are a dozen or more classifications of beneficial uses, specifically in the context of water quality; there are also beneficial uses in the context of water rights and they don’t always overlap.

Click here to read California’s anti-degradation policy.

The California Environmental Quality Act

The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) was enacted in 1970 and is the state’s version of the National Environmental Policy Act. While the specific differences between the federal version and the state version are beyond the scope of this article, both are designed to ensure that projects under the purview of local, state, and federal agencies will not significantly harm the environment.

Click here to learn more about the California Environmental Quality Act.

Regulating discharges to groundwater

The Clean Water Act is largely silent with respect to groundwater and discharges to groundwater, although Dr. Harter noted there was a recent decision by the Supreme Court in a case that occurred in Hawaii that clarified that the Clean Water Act does apply to some degree to groundwater. “You can’t just pour pollution 100 feet from surface water into groundwater and then have it go from groundwater into surface water and circumvent the intention of the Clean Water Act by having a bypass in groundwater, but generally speaking, the Clean Water Act does not regulate discharges to groundwater.”

The State Water Board and the nine regional water boards protect groundwater through regulatory and planning programs. The key elements of this approach include identifying and updating beneficial uses and water quality objectives, regulating activities that can impact the beneficial uses of groundwater, and preventing future groundwater impacts through planning, management, education, monitoring, and funding.

The State Water Board and the regional water boards have numerous programs to address this groundwater quality. Some of them are:

The Land Disposal Program regulates the discharge to land of certain solid and liquid wastes. In general, these wastes cannot be discharged directly to the ground surface without impacting groundwater or surface water, and therefore must be contained to isolate them from the environment. Click here to learn more about the Land Disposal Program.

The Irrigated Lands Program regulates discharges from irrigated agricultural lands. These discharges include irrigation runoff, flows from tile drains, and stormwater runoff. These discharges can affect water quality by transporting pollutants, including pesticides, sediment, nutrients, salts, pathogens, and heavy metals, from cultivated fields into surface waters, or by infiltrating down into the underlying groundwater aquifer. Click here to learn more about the Irrigated Lands Program.

The Central Valley Salinity Alternatives for Long-Term Sustainability (CV-SALTS) is a collaborative basin planning effort aimed at developing and implementing a comprehensive salinity and nitrate management program. The Salt and Nitrate Control Program provides a new framework for the Regional Water Board to regulate salt and nitrate, while also ensuring a safe drinking water supply. While the CV-SALTS program is not directly related to SGMA, there is potential for significant overlap with GSAs implementing their GSPs. Click here to learn more about CV-SALTS program.

The Drinking Water Source Assessment and Protection (DWSAP) Program addresses both groundwater and surface water sources. The groundwater portion of the Program serves as the state’s wellhead protection program as required by the federal Safe Drinking Water Act. The program has two primary elements: Drinking Water Source Assessment and Source Protection. Since 1997, the Program has with the assistance of others—34 counties, the California Rural Water Association, and more than 500 water systems—completed assessments for nearly all the public drinking water sources in the state. Click here to learn more about the Drinking Water Source Assessment and Protection Program

Department of Pesticide Regulation’s Groundwater Protection Program

DPR’s Groundwater Protection Program evaluates and samples for pesticides to determine if they may contaminate groundwater, identifies areas sensitive to pesticide contamination, and develops mitigation measures to prevent that movement. The Department also adopts regulations and does outreach to carry out those mitigation measures. The measures are designed to prevent continued movement to groundwater in contaminated areas and to prevent problems before they occur in other areas.

County ordinances

California cities and counties can use their police powers to regulate both the construction of wells and pumping of groundwater. For example, a city or county may adopt a discretionary well permitting scheme authorizing the agency to approve or deny a well permit or restrict the export of groundwater outside the county.

SGMA extends the authority to regulate or limit the amount of water that an individual may extract from the groundwater supply to any local agency that becomes a basin’s groundwater sustainability agency (GSA).

Here are some examples of county ordinances:

Groundwater regulation: An analogy

Dr. Harter said that water quality regulations are much like a speed limit. To set the speed limit, someone must have done a risk assessment at one point to determine where the risk is highest and to set the speed limit. They may have even considered that trucks create a higher risk and other moving objects create a lower risk, and so trucks may have a different speed limit than cars, while pedestrians don’t have a speed limit.

“So there is this prioritization among parties,” he said. “You see a similar prioritization that comes out risk assessments with respect to polluters of groundwater or surface water where we make these decisions about which pollution sources we want to focus on in order to really get a handle on it.”

There is also a responsible party. “For speed limit, you as the driver are responsible. You as the driver also have tools: you have your best management practices to control your speed, you have a brake pedal, you have a gas pedal, but most importantly, you also have a speedometer to read how you’re doing when you’re driving which is your feedback. Then there is the regulatory enforcement which in the case of the speed limit is a random control through a cop that has a radar gun.”

It is done very similarly with water quality regulation. For instance, there are a lot of underground storage tanks at gas stations that have been leaking which has been prioritized as an important source to control. “They now have best management practices to control that pollution,” he said. “They have a double-walled tank instead of a brake pedal, and then they have a concrete encasing around it, and the speedometer here is a leak detection device that might be inside the tank and another leak detection device outside the tank which are the speedometer for the gas station owners who is the driver or the responsible party.”

The enforcement is the monitoring wells that are located up gradient and down gradient from the potential or active pollution sources. “Monitoring wells are the gold standard for regulatory control of pollution sources in groundwater,” he said. “Monitoring surface water on a regular basis at locations upgradient and downgradient from discharge points like wastewater treatment plants is a standard practice that we have come to over the past 50 years. So we do have permitting programs for point sources of pollution with respect to groundwater under Porter-Cologne.”

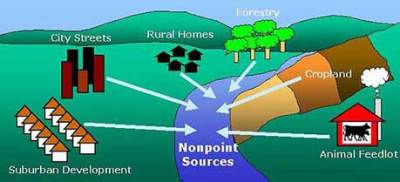

Non-point pollution sources

Non-point pollution sources do not have one particular location where it is discharged; rather, there are many locations or locations that are continuous in space. These include agricultural discharges, fertilizer, pesticides, salts, sediments, and also urban stormwater runoff which has all kinds of potential contaminants that are nonpoint sources of pollution. Nonpoint sources often cover millions of acres.

Runoff is a major cause of nonpoint-source pollution. In cities, as rain flows over the asphalt, it washes away oil, tire particles, dog waste, trash, and other contaminants, flushing them into a storm drain and dumping them in a river or waterway. In rural areas, runoff can wash sediment from the roads in a logged-over forest tract or an area impacted by wildfire. It can also carry acid from abandoned mines and flush pesticides and fertilizer from farm fields. All of this pollution is likely to wind up in streams, rivers, lakes, and groundwater.

The Clean Water Act doesn’t really have a permit program per se for nonpoint sources; instead, it has the Total Maximum Daily Load program, which is a large regulatory program that brings nonpoint sources into negotiations over best management practices including practices in making sure that surface water quality is not unduly degraded by pollution from nonpoint sources. The TMDLs mainly apply to surface water quality, not really groundwater.

In California, under the Porter Cologne Act, nonpoint sources were first given a waiver or an exception; they did not have to obtain a permit. That waiver or exception went away in 1998 when a law was passed that the waivers were to end by 2002.

“The regional water boards which had, for 30 years, focused on groundwater pollution from point sources, now had to start to look at groundwater pollution from nonpoint sources for the first time,” said Dr. Harter. “Since 2002 , a number of new programs been established to deal with both urban and agricultural discharges to groundwater, such as the Dairy Order in 2007, the Irrigated Lands Programs, and the agricultural orders that are in place in the Central Valley and the Central Coast region.”

A 2009 order from the State Water Board required all 9 regions basin plans to consider nitrate and salt sources from both nonpoint sources and point sources and both to surface water and to groundwater. Those plans are starting to be amended, most recently in the Central Valley, where the Central Valley Salt and Nutrient Management Plan that has just been recently approved and is starting to begin implementation.

“A lot of nonpoint sources discharge by default,” Dr. Harter said. “We can’t stop leaking out of cities; we can’t stop leaking out of the agricultural landscape. It’s a matter of how we manage it. It happens on a regular basis and it happens on a spatially continuous basis, but every field is different, every part of the city is different, every business is different, and so that’s something we struggle with. It’s a new frontier.”

Enforcement, especially for groundwater quality, has been monitoring wells. For surface water quality, it’s water quality measurements in the streams. However, it’s not practical for to have monitoring wells next to every field in the agricultural landscape, so for the agricultural discharges, there is a combination of different information systems that provide information and monitor this.

“It’s on one hand looking at nitrogen budgets at farms, and on the other hand, having a regional trend monitoring program that can look at long-term trends in space also and in time of water quality, provide assessments, and an active program to develop management practices that are going to be less harmful for groundwater,” said Dr. Harter. “All of these have a lot of activity going on. This is reflecting what happened in the 1970s and 1980s with Clean Water Act coming on board when we spent a lot of money and time on how to improve wastewater treatment, and wastewater treatment practices, which was a point source at the time and regulated under the Clean Water Act.”

“It’s on one hand looking at nitrogen budgets at farms, and on the other hand, having a regional trend monitoring program that can look at long-term trends in space also and in time of water quality, provide assessments, and an active program to develop management practices that are going to be less harmful for groundwater,” said Dr. Harter. “All of these have a lot of activity going on. This is reflecting what happened in the 1970s and 1980s with Clean Water Act coming on board when we spent a lot of money and time on how to improve wastewater treatment, and wastewater treatment practices, which was a point source at the time and regulated under the Clean Water Act.”

With the point source permits, there is usually an individual permittee, such as a wastewater treatment plant that discharges into a stream that’s regulated by the regional water board. With nonpoint sources, dischargers have formed agricultural coalitions and their members collect information that then gets aggregated by the coalition; the coalition manages these management evaluation programs and the trend monitoring program and also prepares the groundwater assessment report as part of the coalition’s groundwater quality management plan. It is in many ways similar to the permits that an individual would have where an individual would have similar responsibilities.

Learn more about how the State Water Board controls nonpoint source pollution by clicking here.