The Delta Reform Act expressly defined the state’s water policy priorities as they relate to the Delta, including the express recognition that given the interconnected nature of the Delta with the water use patterns of large parts of Northern, Central, and Southern California, the Delta crisis cannot be resolved by taking action in the Delta alone. Achieving the coequal goals of statewide water supply reliability and restored Delta ecosystem is expected to be done, in part, through compliance with the state’s policy to reduce reliance on the Delta and related mandate to improve regional self-reliance. In order to achieve these goals, regions located inside and outside the Delta must take action to increase water efficiency and develop sustainable local and regional sources of water, which will contribute to improved water supply reliability.

In 2018, the legislature passed AB 1668 and SB 606, which establish guidelines and standards for urban and agricultural water use efficiency and conservation and a framework to implement those standards and provide oversight. The primary goals of the legislation are to use water more wisely, eliminate water waste, strengthen local drought resilience, and improve agricultural water use efficiency and drought planning. To implement the legislation, DWR and the Water Board are working together to develop a framework of new standards for indoor and outdoor residential water use; commercial, industrial, and institutional (CII) water use for landscape irrigation with dedicated meters; and water loss from distribution systems.

It’s important to note that the 2018 legislation applies to the actions of DWR, the State Water Board, and water suppliers. It does not set any standards or rules for individual use.

At the August meeting of the Delta Stewardship Council, council members received an update on the State Water Board’s ongoing efforts to implement the legislation from Charlotte Ely, a Supervising Senior Environmental Scientist at the Water Board, who gave an overview of the legislation and an update on the development of the water efficiency standards.

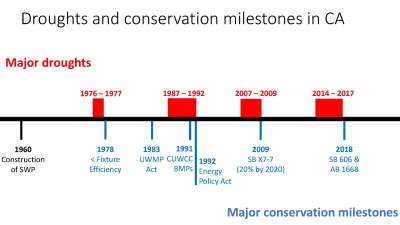

Charlotte Ely began by noting there is a pattern in California of major conservation legislation being passed following major droughts.

Charlotte Ely began by noting there is a pattern in California of major conservation legislation being passed following major droughts.

After the short but intense 1976-77 drought, California began regulating plumbing fixture efficiency for the first time.

After the 1987-1992 drought, there were various attempts to regulate fixture efficiency in California and many other states pushed the federal government to create a national standard for water-using products by the Energy Policy Act of 1992. Toilets for example would have to use no more than 1.6 gallons per flush. At this time in California, large suppliers and environmental groups signed an MOU to implement conservation best management practices. The California Urban Water Conservation Council oversaw this MOU for two decades.

After the 2007-09 drought, the legislature passed SBX7-7 directing water agencies to reduce water by 20% by 2020.

And then during the most recent drought, 2014-17, California set mandatory reductions for the first time in the state’s history. After the drought ended, the legislature passed SB 606 and AB 1668, directing suppliers, farmers, and state agencies intended to make conservation a California way of life.

“There is another pattern in California, another place that is episodically struck by drought,” said Ms. Ely. “We call it the ‘hydro-illogical cycle’. During a drought, people become aware of their water use and step up to save water in big and small ways. Maybe we even pass legislation to keep everyone on the right track, but when rain comes, everyone is relieved and we return to our pre-drought routine.”

However, this is only one part of the story and it’s not entirely true, she said, presenting a graph from of total and per capita water use in California from 1960 to 2015 (upper right) from a Pacific Institute report using data from the Department of Water Resources.

“As you can see, water use went down during each major drought and then started to creep back up again, as shown by the blue production columns,” she said. “But pay attention to the green line. Even though we see some rebound after the 2007-09 drought, statewide per capita water use has been declining. As a state, we have underestimated the impact of water efficiency and are observing a flattening of demand. In many cases, our assumptions were wrong. More people did not lead to greater demand.”

Another recent Pacific Institute report found that urban water suppliers in California have routinely overestimated long-range water demand forecasts between 2000 and 2015. Those overestimates were such that water suppliers projected that future water demand would increase when actual demand was and has been declining.

The graph to the right picks up where the Pacific Institute graph left off using data from the monthly conservation and production reports that the retail water suppliers have been submitting to the water board since the summer of 2014. She noted that the numbers do not align perfectly because the Department’s data includes things such as water for energy generation and water drawn from private wells.

The graph to the right picks up where the Pacific Institute graph left off using data from the monthly conservation and production reports that the retail water suppliers have been submitting to the water board since the summer of 2014. She noted that the numbers do not align perfectly because the Department’s data includes things such as water for energy generation and water drawn from private wells.

On this graph, the blue/purple bars represent relatively cool years, the red bars are hot and dry years, and green is per capita water use.

She noted that in 2017, while a wet year, was also the year drought restrictions were lifted and water use increased, likely because Californians eased off emergency conservation tactics like letting lawns go brown. In 2019, a wet year, statewide water use and GPCD declined as outdoor water needs declined.

“In short, while Californians are using more water than they were during the recent drought, we appear to be continuing the trends shown on the previous slide,” Ms. Ely said. “We are making conservation a California way of life.”

SB 606 and AB 1668 establish a new foundation for long term improvements and water and conservation and drought planning and were the direct outcome of Executive Order B-37-16 issued during the recent drought. The Executive Order marked a turning point in the state’s drought response that emphasized the need to go beyond temporary drought measures and adopt permanent changes to use water more wisely and prepare for more frequent and persistent periods of limited supply. The Executive Order acknowledged that increasing long term water conservation and water use efficiency are critical to California’s resilience to drought and climate change.

SB 606 and AB 1668 establish a new foundation for long term improvements and water and conservation and drought planning and were the direct outcome of Executive Order B-37-16 issued during the recent drought. The Executive Order marked a turning point in the state’s drought response that emphasized the need to go beyond temporary drought measures and adopt permanent changes to use water more wisely and prepare for more frequent and persistent periods of limited supply. The Executive Order acknowledged that increasing long term water conservation and water use efficiency are critical to California’s resilience to drought and climate change.

The recommendations in an April 2017 report, Making Water Conservation a California Way of Life, and subsequent legislative outreach greatly informed the development of the 2018 conservation legislation. The resulting framework focuses on four primary goals: using water more wisely, eliminating water waste, strengthening local drought resilience, and improving agricultural water use efficiency and drought planning. She noted that the bulk of the legislation relates to achieving the goal of using water more wisely.

Ms. Ely acknowledged that the Delta Plan supports increased water conservation and efficiency as one of the core strategies to provide a more reliable water supply for California.

Ms. Ely acknowledged that the Delta Plan supports increased water conservation and efficiency as one of the core strategies to provide a more reliable water supply for California.

An important part of the legislation is determining the urban water use objective, which is defined as the estimate of aggregate efficient water use for the previous year, based on adopted water use efficiency standards and the local service area characteristics of that year. The urban water use standard is the total of the items listed on the slide, including variances and a bonus incentive which can equal up to 15% of the objective.

“The takeaway that I want to leave you with from this slide is that we will be customizing objectives based on local conditions and every community is different and the objectives will reflect that,” she said.

The slide at the lower right shows the general timeline for developing and implementing the standard. Right now, the Department and the Water Board are working on developing standards and regulatory documents. The Water Board is directed to adopt the rulemaking by June 30, 2022. Starting in 2024, retail water suppliers calculate their urban water use objectives and by 2027, the ambitious goal is that suppliers will have reached their objectives. 2027 is also the first year suppliers could be subject to financial penalties.

The schematic on the upper right outlines the major actions and products required to implement the 2018 conservation legislation. Department of Water Resources-led actions and products are in blue, the State Water Board-led actions and products are in salmon, legislature is in yellow, and retail water suppliers in green.

The arrow is pointing to one of the first upcoming deliverables. The 2018 conservation legislation directed the Department in coordination with the Board to study whether or not there is a standard for indoor water use that more appropriately reflects best practices. Ms. Ely said that the Department of Water Resources and the State Water Board are working together to try to understand indoor water use trends to consider whether the provisional standard is appropriate and to deliver a required report to the legislature by January 1, 2021.

“The legislature provisionally set the indoor standards at 55 gallons per capita per day until 2025, at which point it would decline to 52.5 and then to 50 after 2030,” she said. “The 55 gpcd is for indoor use, is actually a relic of the SBX7-7 planning process. Rather than create a new indoor standard, the legislature borrowed from what is referred to as Method 2. However, existing research shows that residential water use has already been declining.”

“The legislature provisionally set the indoor standards at 55 gallons per capita per day until 2025, at which point it would decline to 52.5 and then to 50 after 2030,” she said. “The 55 gpcd is for indoor use, is actually a relic of the SBX7-7 planning process. Rather than create a new indoor standard, the legislature borrowed from what is referred to as Method 2. However, existing research shows that residential water use has already been declining.”

Ms. Ely referenced a recent July LA Times article that found that annual water use by the city of LA has stabilized at the lowest levels in nearly half a century. “In LA, there were significant gains in water use efficiency from plumbing codes, landscape ordinances, and rebate programs that have helped to reduce today’s per capita water use to 40% lower than it was in 1970 levels, so even as Southern California grows, water use has declined. How much indoor use has declined and how much more it will and should decline in the coming years will be the focus of this January 2021 report to legislature and our subsequent rulemaking document.”

To implement the 2018 conservation legislation well, the indoor standard needs to be reasonable as a value that is too high would render the framework meaningless while a value is too low would be a heavy burden for urban retail water suppliers, she said.

“Based on the CA Energy Commission standard for water-using fixtures and appliances, efficient water use would probably be about 35 gallons per capita per day which is roughly where the city of Santa Cruz is. But is 35 gpcd a practical and achievable indoor water use standard for all of California within the timesteps outlined by the legislation? With more and more accurate timely data, we’re developing a more nuanced understanding of water use and water use trends which will not only inform the 2021 legislative report but also long-term water management generally.”

The State Water Board was directed to adopt the efficiency regulation by June 30, 2022, and in order to meet that deadline, the Board needs to initiate the rulemaking process by June 2021, so Board staff are developing the regulatory documents now, working to understand and document potential environmental and economic impacts. They are working with a team of CSU and UC researchers to evaluate impacts using a scenario-based approach that reflect different assumptions about the economy, climate, and standards.

“We’ll consider perspective costs like those outlined on the slide,” she said. “If existing conservation remains the same, costs would be minimal. The box on the right outlines some perspective costs if Californians become less efficient, such as increased water rates or increased dry weather runoff because of over irrigation. The box on the left outlines some costs we could incur as Californians become more efficient, so for the different scenarios, we will consider costs like these.”

They will also evaluate perspective benefits which she noted if existing conservation remains the same, the benefits would be minimal.

Ms. Ely noted that initially in the legislation, they were directed to submit their first urban water use objective by January 1, 2023, but subsequent legislation delayed this to 2024.

This slide shows the progressive enforcement policy of the State Water Board which was specified in the legislation.

This slide shows the progressive enforcement policy of the State Water Board which was specified in the legislation.

She noted three key issues: “The State Water Board will not fine or that is issue what is called an Administrative Civil Liability on an urban retail water supplier that fails to meet its objective until 2027. Another key point here is that it is urban retail water suppliers that are the entities subject to enforcement, not individuals and not individual parcels. And then lastly, urban retail water suppliers must comply with the overall objective, not with the individual standards I described on the earlier slide.”

Ms. Ely then gave her concluding thoughts. “Yesterday I was emailing one of your staff and he asked me, with the implementation of the requirements, what could we see change? Could a possible outcome be a reduced reliance on water supply from Delta exports? And the answer is, I don’t know yet and I don’t think anyone does. The 2018 legislation provides a flexible framework. Part of that flexibility is due to the ambiguity of key terms and directives which gives the Department and the State Water Board a fair amount of discretion. How we proceed will determine the regulation’s impact. Our two agencies are closely coordinating to ensure this new framework works and works well for California, so I invite you to follow the development of the Department’s recommendations and the State Water Board’s rulemaking to help us make sure that we adopt supports your agency’s important work.”

Anthony Navasero, Senior Water Resources Engineer, then briefly discussed the interface between the Delta Plan and the water conservation and efficiency legislation.

There are three recommendations in the Delta Plan that support the implementation of the legislation:

WR R1: Implement water efficiency and water management planning laws, recommends that water suppliers fully implement applicable water efficiency and water management laws, including required reporting in urban and agricultural water management plans.

WR R6: Update water efficiency goals, recommends that DWR and Water Board identify and implement measures to reduce impediments to achieve state water conservation, recycled water, and stormwater goals, as well as recommends agencies address water distribution system leakage.

WR R16: Supplemental water use reporting, recommends that the water rights holders submit reports on the development and implementation of all water efficiency, water supply projects, and net consumptive use.

“The conservation as a way of life legislation and the resulting conservation and efficiency standards and reporting requirements are examples of how DWR and the water board are implementing the Delta Plan recommendations that support reduced reliance on Delta water supplies,” concluded Mr. Navasero.