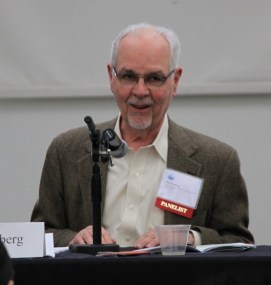

Panel at the California Water Law Symposium features Jay Lund, Ellen Hanak, Phil Isenberg, and Erik Vink

Panel at the California Water Law Symposium features Jay Lund, Ellen Hanak, Phil Isenberg, and Erik Vink

The Delta is many things to California: It is the largest estuary on the West Coast and is home to hundreds of species, both native and non-native; it is a productive agricultural region; it is a popular recreation area for boaters and for fishermen; and it is the hub of California’s water system through which a significant portion of the state’s water supplies must pass. And the Delta’s woes are similarly numerous: crashing native species populations, invasive species, concerns over aging levees, and water quality issues, as well as impacts from climate change.

With so many competing objectives, finding a path forward for the Delta has long been a challenge. The 2009 Delta Reform Act requires the state to manage the Delta for the coequal goals of providing a reliable water supply for California, and improving the health of the Delta ecosystem while maintaining it as a cultural, recreational, natural and agricultural resource. But how can we achieve the coequal goals?

In this panel discussion from the recent California Water Law Symposium, Ellen Hanak, Director of the Public Policy Institute of California’s Water Center; Phil Isenberg, retired Chair and Vice-chair of the Delta Stewardship Council; and Erik Vink, Executive Director for the Delta Protection Commission discuss the future of the Delta. The panel was moderated by Jay Lund, Director of the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences.

“There are a lot of people that depend on the Delta,” began Jay Lund. “Except for Marin County, pretty much all of the Bay Area is dependent upon Delta water, almost exclusively either directly out of the Delta from the State Water Project, the North Bay Aqueduct, or the Contra Costa diversions, or from upstream diversions on the Mokelumne River and Tuolumne River.”

Mr. Lund then gave some background on how the Delta was formed. “The Delta is a creation of sea level rise since the last Ice Age,” he said. “At the end of the last Ice Age, the Delta was outside the Golden Gate; the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers was a dry confluence coming together and went through the Bay, which wasn’t a Bay then, it was just a river flowing out the Golden Gate towards the Farallons, and that’s where the Delta was. As the sea level rose, that Delta moved upward and landward in space and time until about 6000 years ago, the sea level was sufficiently high to be where it is today. And since that 6000 year period, the steady rise of the sea level is what built the peat soils, and it’s those same peat soils that have subsided as they have been diked and drained for the last 150 years, that are now 10 to 25 foot below sea level.”

Mr. Lund then gave some background on how the Delta was formed. “The Delta is a creation of sea level rise since the last Ice Age,” he said. “At the end of the last Ice Age, the Delta was outside the Golden Gate; the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers was a dry confluence coming together and went through the Bay, which wasn’t a Bay then, it was just a river flowing out the Golden Gate towards the Farallons, and that’s where the Delta was. As the sea level rose, that Delta moved upward and landward in space and time until about 6000 years ago, the sea level was sufficiently high to be where it is today. And since that 6000 year period, the steady rise of the sea level is what built the peat soils, and it’s those same peat soils that have subsided as they have been diked and drained for the last 150 years, that are now 10 to 25 foot below sea level.”

One of the problems of the Delta is the land subsidence in much of the west and central Delta, he said. “Imagine the Delta; you have the water level rising with sea level, and you have the land level subsiding as we diked and drained and worked on those soils. You’ve all taken advanced fluid mechanics I’m sure, we know how this story ends. We know what the end looks like but we don’t know the process by which it’s going to come, so we have some really fundamental issues in the Delta in quite a few ways. And it is all due to climate change over the last 10,000 years and the coming climate change will affect it still.”

There have been state and federal governmental processes concerning the Delta; there have been government engineers, scientists, and lawyers, all thinking about how to manage the Delta since the 1920s. There are some insightful reports worth reading for the perspectives, which in some ways, not much has changed, he said. “This process of steady government examination has continued until the present day where have 200 different government agencies working on the Delta now. But in recent times, we have focused a lot on what was the Bay Delta Conservation Plan or BDCP, which has morphed in the last two years to be the California Water Fix.”

The panelists then were given a few minutes to speak to kick off the discussion.

Ellen Hanak began by recalling how she had been thinking about the decades that she has been working with Jay Lund and Phil Isenberg. Their first collective book, Envisioning Futures for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta came out in 2007, which was about the same time Phil Isenberg began as chair of the Delta Vision Blue Ribbon Task Force, and just after the start of the Bay Delta Conservation Plan.

“So we have about a decade, it was after a period where there was hope for consensus in the 90s up through the early 2000s on doing something in the Delta that did not involve new infrastructure through the CalFed process; the theme there was ‘we can all get better together,’” she said. “There was sort of a temporary peace among the various parties – the folks depending on the exports, the folks depending on upstream diversions, the folks in the Delta, and environmental interests. There was sort of a period of consensus that started to break down around 2004-05 when it became clear that what was happening was really not great for the listed fish species in the Delta.”

“So we have about a decade, it was after a period where there was hope for consensus in the 90s up through the early 2000s on doing something in the Delta that did not involve new infrastructure through the CalFed process; the theme there was ‘we can all get better together,’” she said. “There was sort of a temporary peace among the various parties – the folks depending on the exports, the folks depending on upstream diversions, the folks in the Delta, and environmental interests. There was sort of a period of consensus that started to break down around 2004-05 when it became clear that what was happening was really not great for the listed fish species in the Delta.”

The Pelagic Organism Decline, or the sharp drops in population of native species in the Delta spurred a crisis in the mid-2000s that spurred thinking about doing things differently in the Delta. So Ellen Hanak, Jay Lund, along with Peter Moyle, Richard Howitt, Bill Fleenor, and Jeff Mount looked at where the Delta was headed, considering the levees and what that means for water supply and reliability as well as the economy of the region, but also how water is being managed and what that means for the native species. The book, Envisioning Futures for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, looked at nine possible alternatives, thinking about the different ways that the system can be managed for water supply and for the ecosystem, and in relation to that what impacts that would have on the local Delta economy as well.

“We didn’t pick a winner there, but we did propose that the idea of thinking about replumbing the Delta was one that was worth resurrecting,” Ms.Hanak said. “It’s not a new idea. The projects now just pull the water through the channels in the Delta down to the pumps, and that was recognized from the start as something that was probably not going to be great for critters. There were already proposals back in the 50s and even back to the 40s to possibly have some kind of a different diversion. There was a big effort for the peripheral canal that was stopped in the early 80s by a referendum, even though it had approval at both the state and federal level and it was the third rail for a while after that.”

It was about the same time that the water exporters and the state started the process for the BDCP. “What we suggested then was that it was promising as a way of thinking about remanaging the system and possibly being able to better meet the different goals that society had in terms of water supply reliability and environmental health of the system,” she said.

At the time, the book got a lot of traction and Ms. Hanak felt a lot of optimism. “My sense was that people were willing to think about working together differently to manage this system,” she said. “I’m kind of feeling ten years out from that that we’ve made a lot of progress in some ways in terms of establishing coequal goals for the Delta as state policy, but I also feel less optimistic about the trajectory. That’s because I feel like it’s been hard for us as a multiple communities to come together and agree on what a game plan could be and have confidence in the governance to implement that game plan in a way that does address the coequal goals in a way that people generally conceive of as a fair in terms of balancing, while considering the folks that live in the Delta.”

Phil Isenberg began by noting that California joined the union in 1850. “So we have 167 years of experience with endless laws, endless regulations, endless voter proposals, endless court decisions of various types, and endless political speeches in sum total adding up to everyone in society being promised all the water they want, whenever they want it, regardless of the circumstance, for whatever purpose they use it,” he said. “It should not surprise anyone that that looks like chaos and confusion after 167 years.”

“You might want to go back to the 95th law enacted by the first legislature in 1850, the one that incorporated the British common law into California,” he continued. “Its clarity, its precision, and its implications are just gorgeous. And – this is almost a direct quote. ‘If not repugnant to the constitution of the US, or the constitution or laws of the state of California, the common law should be incorporated in California.’ What delicious terminology. What ever happened to lawyers who would write things like ‘if not repugnant to?’ But that lack of precision – or perhaps a better way to put it is a notation that you can pass a new law and the British common law falls off the chart if done appropriately is an exemplar of all of the laws that have gone on.”

“You might want to go back to the 95th law enacted by the first legislature in 1850, the one that incorporated the British common law into California,” he continued. “Its clarity, its precision, and its implications are just gorgeous. And – this is almost a direct quote. ‘If not repugnant to the constitution of the US, or the constitution or laws of the state of California, the common law should be incorporated in California.’ What delicious terminology. What ever happened to lawyers who would write things like ‘if not repugnant to?’ But that lack of precision – or perhaps a better way to put it is a notation that you can pass a new law and the British common law falls off the chart if done appropriately is an exemplar of all of the laws that have gone on.”

In terms of Delta management, today there is no clear focused coherent management structure in the Delta, there never has been, probably will not be in any measure in the very near future, he said. “There is a mish mash of federal and state agencies and entities with local agencies, all of whom follow their own statutory direction or their own policy preference or the leadership that they get from their political bosses, and all of the public agencies are endlessly harassed by many of the people in this room who spend their time trying to shape their decisions or stop their decisions, whatever it is.”

Mr. Isenberg said he was astonished when in 2009, the legislature passed The Delta Reform Act, which was a series of bills, one of which established the Delta Stewardship Council and directed the Council to develop a legally enforceable Delta Plan for management of the Delta. “Contained within the statute was the thing called the coequal goals; I plead guilty for having a share of thinking up the title, ungrammatical as it is,” he said. “The coequal goals simply declares that a reliable supply of water for Californians and an improved, restored, and protected Delta ecosystem are coequal. All the parties who received that liked it in the abstract because they could draw from the lesson that as long as they are now coequal, what they prefer to have done will be done to the exclusion of everything else, which wasn’t how it worked out.”

The Council did develop and adopt the Delta Plan unanimously, and within 30 days, we were sued by 27 organizations on all sides of the issue, Mr. Isenberg said. “The sum total of the litigation was you went too far or you didn’t go far enough, and it should not surprise you that when water contractors, agricultural interests, and environmental interests and some local interests in the Delta all say that, they mean substantially different from each other.”

It took 18 months to get a preliminary decision by a Sacramento Superior Court judge in late 2015, which essentially dismissed the arguments by the federal and state water contractors, but did say that the Delta Plan as adopted was insufficient in clarity on either water conveyance or storage, and had to be rectified. In a subsequent clarification order, the court said the Council can’t do anything else until that’s done, he said. “Now in the current configuration of California trying to do coherent planning in the midst of all this interest group clutter, the court essentially stopped the activity.”

The California Water Fix and the Eco Restore program don’t do much of anything on management because they are largely facility discussions in the traditional way we talk about water projects, Mr. Isenberg said. “But some people like the notion that since the state and federal agencies have to be consistent with the Delta Plan, perhaps no progress can be made on Water Fix or Eco Restore until the Delta Plan is completed and gone through the review process. I’m not so sure about that, but it’s a maybe.”

“The management of the Delta is just boring good government, that’s my view,” he said. “It’s not inherently interesting, it’s just boring good government. It’s an attempt to get people like me out of the mix and let engineers and scientists kind of tackle all the problems of water and the ecosystem without interference from policy makers. That will happen when it is reasonably clear to politicians they cannot win the ultimate fight of making all of their voters always happy with them for all times by promising to give water out, because pesky nature is just trying to screw us all up (just witness the recent drought). So society simply is going through the problem of what do you do if there’s not enough to give every one everything they want every day of the year. And the answer is you get less. The management answer would be, let’s all share in the reductions so it’s a soft landing. The human reaction is me me and my friends first, and somebody else can do whatever they want to do.”

Mr. Isenberg then closed with his thoughts on the future of the Delta Plan. “I predict that as the Council’s appeal goes forward, in about two years, some courts are essentially going to start looking around and trying to find evidence that the legislature actually meant an enforceable Delta Plan to control some actions of state and local agencies. That will start popping up as one of the tools to be used, but it will not create a single management structure for the future because this is America, and we don’t believe in that stuff.”

Erik Vink then offered a perspective from the Delta region. He began with describing what the Delta Protection Commission does. “The Commission is a regional agency of sorts. Our only real authority is over local land use decisions within the Delta region, and the Delta region is largely agricultural. The edges of the Delta are urbanized and urbanizing. There are portions of the city of Sacramento, city of West Sacramento, Stockton, Tracy, Manteca, Lathrop, all the way into the Contra Costa cities of Oakley, Brentwood, Pittsburgh, and Antioch that are part of the legal Delta, but they are at the very periphery of the Delta. Most of what we know is the Delta is the great interior which is almost entirely agricultural, or waterway, or lands that are natural, either having been restored or intended to be restored. So our authority is really over that interior of the Delta where there isn’t a lot of land use change anyway, so that role is a rather limited one.”

“Our more important role is to serve as voice for the Delta region and Delta interests,” he continued. “We are a state agency but an unusual one in that our membership is almost entirely composed of local officials from throughout the Delta region. Eleven of the fifteen commission members that I work for are local officials from the Delta region: county supervisors, city council members, water agency officials, and we have four state agency members as well, so it makes for very interesting discussions. Not always unanimous votes, but for the most part, understanding that we’re there to serve as voice for the Delta region.”

“Our more important role is to serve as voice for the Delta region and Delta interests,” he continued. “We are a state agency but an unusual one in that our membership is almost entirely composed of local officials from throughout the Delta region. Eleven of the fifteen commission members that I work for are local officials from the Delta region: county supervisors, city council members, water agency officials, and we have four state agency members as well, so it makes for very interesting discussions. Not always unanimous votes, but for the most part, understanding that we’re there to serve as voice for the Delta region.”

Mr. Vink noted that Phil Isenberg referenced the coequal goals only partly. “We do have coequal goals for the Delta, reliable water supply and restore the Delta ecosystem, but the statute says that those coequal goals are to be accomplished in a manner that protects and enhances the unique Delta values – agricultural, historic, the cultural values of those historic communities, recreational values, and the natural resource values of the Delta. So if there’s one thing you take from this discussion today, and you’re going to hear coequal goals a lot, remember that the coequal goals are to be accomplished in a manner that protects and enhances the unique Delta values.”

That is the biggest problem with the more recent proposals for fixing the water supply reliability problem. “Understandably, huge enormous twin Delta tunnels do a great job of addressing water supply reliability for the export regions, but I’ve yet to hear a good explanation of how those protect and enhance the unique Delta values, and that’s the primary concern that we hear throughout our region,” he said.

“So the long term vision, I would argue, is achievement of the coequal goals but not at the expense of the Delta region, and we’re not there yet. Avoiding actions that would not protect and not enhance those Delta values. Ensuring that the Delta enjoys sufficient water quality for agriculture and for in-Delta needs, and this is not just in water code section 85054, this is in other parts of California statute. This is the law for California.”

The Delta region doesn’t ignore the coequal goals, Mr. Vink said. “We understand it’s state law, it’s what we must work to accomplish; it’s what the Delta Plan is all about, but again with the proviso that the Delta values are protected and enhanced. If there’s one thing I’d like to leave you with, it’s just an understanding and acknowledgement that the Delta is a place, there are people there who have made lives for generations, there are historic communities, there are recreational values that are supreme in our state and that we continue to keep those in our minds, if not at the fore of our minds as we’re working on solving the thorny problem of a more reliable water supply and restoring the Delta ecosystem.”

Moderator Jay Lund then turned to the future of the Delta. He noted there was about two years left in the current Governor’s administration; then there will be a new first-term Governor; there is a new federal administration which will be different in many ways; and there is the California Water Fix which makes strategic changes in the Delta for water supply reliability; something of a less strategic program of activities for restoration with Eco Restore; and a Delta Levee Investment Strategy on the Delta levees to keep the Delta as a place. “So the first question to the panel is, in this remaining two years, is there room for a grand compromise on the Delta to move some of those strategic issues forward? Or will we be stuck essentially with the kind of incrementalism that we’ve gone through for the last 30 years on Delta management? And if there is room for a strategic compromise in the Delta, how might we get there?”

Moderator Jay Lund then turned to the future of the Delta. He noted there was about two years left in the current Governor’s administration; then there will be a new first-term Governor; there is a new federal administration which will be different in many ways; and there is the California Water Fix which makes strategic changes in the Delta for water supply reliability; something of a less strategic program of activities for restoration with Eco Restore; and a Delta Levee Investment Strategy on the Delta levees to keep the Delta as a place. “So the first question to the panel is, in this remaining two years, is there room for a grand compromise on the Delta to move some of those strategic issues forward? Or will we be stuck essentially with the kind of incrementalism that we’ve gone through for the last 30 years on Delta management? And if there is room for a strategic compromise in the Delta, how might we get there?”

Ellen Hanak began by noting that she and her colleagues Jeff Mount and Brian gray penned an op-ed in the Sacramento Bee titled, A grand compromise for the Delta, which reflected in some ways discussions they’d been having with a larger group of colleagues working in the Delta. “There are some pretty good reasons for having flexibility in how you manage water exports in the Delta, so the idea of having intakes up on the Sacramento River as a way of moving some of the export water to the Bay Area, the San Joaquin Valley, and Southern California is a good idea from a standpoint of water supply reliability in the event that Delta levees collapsed in an earthquake or something like that,” she said. “It’s also a good idea from the perspective of ecosystem management because you’d have a couple of intakes in the south Delta as well as in the north Delta, and you’d have some flexibility and can do less harm to the critters that live in the estuary.”

“The devil on making that work to satisfy coequal goals is in the details,” Ms. Hanak said. “There are trade-offs in getting a deal on the tunnels, because if they are large as they are now proposed to be, there are a number of folks that are concerned that they might not be operated in a manner that’s sufficiently protective of the ecosystem and of water quality in the Delta, no matter what the documents say about upholding all those laws. So that’s sort of one consideration that we had.”

“The devil on making that work to satisfy coequal goals is in the details,” Ms. Hanak said. “There are trade-offs in getting a deal on the tunnels, because if they are large as they are now proposed to be, there are a number of folks that are concerned that they might not be operated in a manner that’s sufficiently protective of the ecosystem and of water quality in the Delta, no matter what the documents say about upholding all those laws. So that’s sort of one consideration that we had.”

The other consideration was that the ecosystem and native species have continued to deteriorate substantially over the last decade. “Peter Moyle is now speaking regularly to the press and in scientific forums about the Delta smelt being functionally extinct in the wild, and there are some other species that are also right at that point,” Ms. Hanak said. “So one has to ask the question, is just rejiggering how we’re managing the water going to be enough for actually restoring those species or do we need to think about a different strategy?”

“Peter Moyle has been leading the thinking for some years now on really moving toward ecosystem based approaches to management and away from single species focus to ecosystem management,” Ms. Hanak continued. “He was the lead author of a report that we all were involved with in 2012 called, Where the Wild Things Aren’t: Making the Delta a Better Place for Native Species (http://www.ppic.org/main/publication.asp?i=1025 ). The idea there was saying you have to think more strategically about how to manage for ecosystem function and this idea of reconciliation ecology. That becomes more and more germane as you’re thinking about how to balance the number of societal goals in a way that can get to some deal of consensus so we’re not just fighting and not doing anything about it.”

There are three pieces to the compromise idea. “One is build one tunnel instead of two,” Ms. Hanak said. “It doesn’t mean you may never need the second tunnel with sea level rise and all of that, but for now, build one tunnel instead of two. It means that for folks that are worried about governance not being good enough to prevent too much water being drawn out of the Sacramento River, it’s a physical limit on it. And you can still can get pretty much all the water as with the two, you just operate bit more to the Delta pumps, and it’s cheaper, too, which is a factor to consider. That first piece got a lot of play in the subsequent editorials and op-eds.”

“The second piece which we view as really critical to the successful future in this system got less play, which is shift the focus of management from single species focus to ecosystem focus, and to do that in a way that gives the environmental managers a water budget that they can manage flexibly and that they can use in ways that can address different kinds of species needs at different times,” she said. “In the context of the Delta, it may also mean not managing for Delta smelt in the wild right now, and recognizing what the scientists are saying about that basically, and using a strategy of conservation hatcheries which we do have in California for biodiversity of the smelt, and looking for opportunities for reintroducing them in places that more suitable within pieces of the broader ecosystem.”

“The third piece is making sure that folks in the Delta feel like they are being paid attention to, and a piece of that is some money for levees,” she said. “Another piece of that could be looking for opportunities for the replumbing of the Delta to provide some water quality benefits to folks in the Delta who have a hard time with that.”

“We said that this could be done,” Ms. Hanak said. “The proposal is consistent with existing law. We think that is definitely true for the piece about ecosystem management with a block of water for the environment; you’d need signoff by federal agencies, but an alternative to that would be Congressional authorization as part of a deal, something like we’ve seen done with the San Joaquin River settlement when you get enough of the parties together to say this is something that we’d like to do.”

“For the Delta smelt piece of it, you’d probably need Congress to sign off on that,” said Ms. Hanak. “Our thinking there is that this is really different from the piece of legislation that just passed which was about restricting what you can do for the ecosystem under the ESA to really looking at making some compromises, recognizing the conditions of the difficulty of restoration for some species right now in the Delta, and that’s part of a broader package of looking at what are our constructive stretched ecosystem goals and have that be the deal, not just sort of whittling away at environmental protection.”

Phil Isenberg said he was intrigued with the idea of a grand compromise, but he noted that Trump’s election minimizes the possibility of compromise for at least two years. “Some of the combatants will simply transfer their interests to Washington, occupy their time under the theory they can get whatever they want there,” he said. “On the other hand, we have no idea what the Trump administration is going to do. We may not like the outcome, particularly, but we don’t know the boundaries of it, and he’s perfectly capable himself of standing up and saying California should solve its own water problems and the feds are getting out of here. That would be a real incentive for trying to do something within the bounds of the state of California.”

“The endangered species act modification, pilot project, or whatever you call it – it’s is intriguing in abstract because in the decade I spent just recently listening to a bunch of people talk, I never once heard any scientist regardless of their position on policy issues, say the Endangered Species Act is a really good scientific way to deal with ecosystem problems – not one,” Mr. Isenberg continued. “It’s a great political tool that you don’t want to surrender too easily, but as a management tool, it’s nuts, that’s my viewpoint.”

“The endangered species act modification, pilot project, or whatever you call it – it’s is intriguing in abstract because in the decade I spent just recently listening to a bunch of people talk, I never once heard any scientist regardless of their position on policy issues, say the Endangered Species Act is a really good scientific way to deal with ecosystem problems – not one,” Mr. Isenberg continued. “It’s a great political tool that you don’t want to surrender too easily, but as a management tool, it’s nuts, that’s my viewpoint.”

“Assuming you could get to that, reducing the size deals with the fact that in the absence of a clear management structure for water and ecosystem together in the Delta, there is no reason to trust the status quo entities whatsoever that they will all kind of follow along to the Delta Plan or much of anything else and just do what needs to be done, so reducing the size is plausible,” he said.

Mr. Isenberg pointed out that four years ago, the Planning and Conservation League, one of the opponents of the tunnel proposal proposed a single 3,000 cfs tunnel and the answer from the water users was that it was not big enough. “I’ve always been puzzled by that,” he said. “When you have one of your major opponents concede that some tunnel ought to be built, why you would say ‘it’s not good enough’ and dismiss it, when you really ought to say, ‘they’ve accepted the concept of the tunnel, we’ll work out the details from there.’ That’s history and that’s gone, but that has a lot of appeal.”

“I think in trying to use this concept of smaller tunnel size (in either capacity or number or both) and ESA pilot projects for lack of any better language, there will be a far greater emphasis on scientific involvement including independent science, and you’re going to wind up forcing the water managers and the eco managers to do most of their planning together, not separately and send letters back and forth about how your other plans don’t really reflect what we’re trying to do. Now that’s hard to do also, but it follows more logically than the first two.”

Erik Vink also said the proposal is intriguing. “We’re appreciative of the recognition of the critical nature of Delta levees and continuing to make improvements in the Delta levee system,” he said. “The levees are critically important, they are absolutely essential to all of those unique Delta values. You don’t have agriculture, you don’t have the historic communities, you don’t have the same recreation without that levee system, so we appreciate that that was a part of the proposal that Ellen and her coauthors put forward.”

Erik Vink also said the proposal is intriguing. “We’re appreciative of the recognition of the critical nature of Delta levees and continuing to make improvements in the Delta levee system,” he said. “The levees are critically important, they are absolutely essential to all of those unique Delta values. You don’t have agriculture, you don’t have the historic communities, you don’t have the same recreation without that levee system, so we appreciate that that was a part of the proposal that Ellen and her coauthors put forward.”

Mr. Vink noted that just as everywhere else, the Commission has a spectrum of opinion, from hardened warriors who say never to those that are a little more reasonable about considering alternatives to the current conveyance system through the Delta. “The Commission has not taken a position on it so I can’t forward any particular official thoughts, but unofficially, I would say these are the types of alternative proposals that we need to be considering and talking about more,” he said.

“The fundamental problem in the Delta region is just a utter lack of trust over how a twin tunnel system would be operated,” Mr. Vink continued. “I understand it would only be operated when there’s excess water, but when you have a physical infrastructure capable of all but draining the Sacramento River, and that infrastructure relies upon water being put into it to pay it off, there’s enormous pressure to maybe bend a little bit on the rules and maybe be a little more flexible and even more and more flexible in how it’s operated. That’s the fundamental trust issue that a smaller infrastructure, frankly a physical constraint, would go a long way towards solving.”

Moderator Jay Lund asked the panelists what they think would happen in the coming years if the California Water Fix is not approved at all. “Will there be a temptation by some of the urban water districts to build their own small tunnel for the Bay Area and Southern California? Certainly they can afford to operate it on their own, they have the technical capabilities. What do you think is likely to happen if Water Fix is not somehow made to succeed – revamped … ?”

Moderator Jay Lund asked the panelists what they think would happen in the coming years if the California Water Fix is not approved at all. “Will there be a temptation by some of the urban water districts to build their own small tunnel for the Bay Area and Southern California? Certainly they can afford to operate it on their own, they have the technical capabilities. What do you think is likely to happen if Water Fix is not somehow made to succeed – revamped … ?”

“Continuation of the status quo,” answered Phil Isenberg. “The ecosystem is going to continue to deteriorate, the problems of salinity in the Delta will increase, but the reality is the upstream water users, all of us pure people in Northern California are using more and more and more water, far more than is exported to Southern California or to the Central Valley and that will continue. All the pressures will converge.”

“Maybe we’re just incapable as a society of acknowledging the limits of natural resources and facing up to the consequences, and prefer to have it happen to us so we can’t be blamed for agreeing to a grand compromise or a change,” Mr. Isenberg continued. “I’m regularly drawn to that conclusion. Everybody used to talk to me all the time in private and say, ‘my guys just won’t understand.’ All that means is you’re acting like a politician. That’s what politicians get criticized for doing, so maybe it’s a psychiatric problem.”

“I think one area there will be progress on is the restoration,” Erik Vink said. “Now maybe restoration won’t proceed as fast as some would like, and the pace of that process is glacial, but there’s renewed focus on it through Cal Eco Restore and a longer term focus on it through emerging Delta Conservation Framework that California Department of Fish and Wildlife is preparing. That I think will continue.”

Mr. Vink noted Metropolitan’s recent purchase of four Delta islands, and noted that between Metropolitan, the Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the Department of Water Resources, they control over 61,000 acres, which is close to 10% of the Delta region. “There’s a large base of land out there that is available and everybody assumes will be used for restoration purposes, but the challenges in getting those restoration projects completed are substantial,” he said. “Maybe that can be short circuited a bit through focus at the highest level of the state government; I don’t know where the federal government will be with this new administration on doing their part to move that forward.”

Mr. Vink noted Metropolitan’s recent purchase of four Delta islands, and noted that between Metropolitan, the Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the Department of Water Resources, they control over 61,000 acres, which is close to 10% of the Delta region. “There’s a large base of land out there that is available and everybody assumes will be used for restoration purposes, but the challenges in getting those restoration projects completed are substantial,” he said. “Maybe that can be short circuited a bit through focus at the highest level of the state government; I don’t know where the federal government will be with this new administration on doing their part to move that forward.”

“We’re continuing to battle over the conveyance, and while I do think there will be continued battles over that, I see opportunity to make advances on the second of the coequal goals,” said Mr. Vink.

“The large urban agencies are making decisions to put a lot of money in much more expensive local supplies, and some of that momentum I think will continue no matter what,” said Ellen Hanak. “In our thinking, it’s also one of the reasons why it could make sense to go to start with one tunnel rather than two, because of the price tag aspect of it.”

“The large urban agencies are making decisions to put a lot of money in much more expensive local supplies, and some of that momentum I think will continue no matter what,” said Ellen Hanak. “In our thinking, it’s also one of the reasons why it could make sense to go to start with one tunnel rather than two, because of the price tag aspect of it.”

Moderator Jay Lund noted that the Water Fix also has implications for California’s other big water problem, groundwater overdraft. “Particularly down in the San Joaquin Valley, groundwater overdraft is prohibited under the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act,” he said. “All those farmers down there are going to become thirstier, and the only other big source of water for them is the Delta. I think Delta water conveyance issues are only beginning to become interesting, from an academic perspective as maybe also from a legal perspective.”

DISCUSSION PERIOD

Audience question: What are the panelists thoughts and what is the status of desalination as one of a source of reducing pressure on the resources of the Delta?

“I used to have a wonderful line that there’s no legal crop that you could afford to water with desalinated water,” responded Jay Lund. “For urban areas, you can find other parts around the world that do it when they are very desperate. It will just double your water bill, essentially.”

“Eighteen months ago, the Carlsbad plant came online in San Diego, and that’s going to be about 8% of San Diego County’s water,” said Ellen Hanak. “It’s pricey and they did that as part of a portfolio, recognizing that it was expensive but they felt like they were at the end of the pipe, and they were willing to pay high money for some low-risk source of water.”

“I think it was also a sign of how little they trusted their own Metropolitan supplies as well,” said Jay Lund. “Issues of trust are everywhere in this decentralized system.”

Audience question: I think it was Phil that said that in the north, they are using a lot more water. Do you think that’s because political regimes or a change in agriculture? Can you talk a little bit more about why we’re seeing that?

“There are some terrific charts that were prepared by the Delta Vision Blue Ribbon Task Force which show that from roughly either 1880 – 1885 up to the present time, the proportion of water that’s being used by in-Delta users, upstream users, exported water, and what flows to the ocean, and what you find is a pretty dramatic and constant increase in the upstream use,” said Phil Isenberg. “Natural growth, development of more agriculture, populations are developing, and of course in an era where you encourage water trades and water marketing, it should surprise no one that the upstream users are hustling a way to find water they can market.”

“One of the really dramatic changes was to find out that the upstream use is greater than the exported water from the Delta, and that’s been true for many decades,” continued Mr. Isenberg. “That is nowhere in the consciousness of Northern California as best I can determine.”

“One of the really dramatic changes was to find out that the upstream use is greater than the exported water from the Delta, and that’s been true for many decades,” continued Mr. Isenberg. “That is nowhere in the consciousness of Northern California as best I can determine.”

“Essentially two-thirds of the water that is diverted from the Delta is diverted upstream of the Delta, including San Francisco and East Bay MUD,” noted Jay Lund.

“It’s availability and cost,” said Erik Vink. “Where water is more expensive than the export water that makes its way to Southern California, then you are just more efficient with your use of it.”

Phil Isenberg recalled that Jeff Mount said many years ago that this isn’t a fight about water; it’s a fight about cheap water. “There’s a lot to be said for the argument that the demands are basically for a water supply that doesn’t cost the user much of anything at all, which is an interesting perspective, if not a driver of policy.”

“I have a wonderful colleague, Richard Howitt, a water economist in California, who says there’s never a shortage of water; there’s only a shortage of cheap water,” said Jay Lund.

Audience question: In regards to the Sacramento and upper watersheds taking growing amounts or volumes of water, do any of you have an opinion on area of use or area of origins laws might be used in to restrict exports that are outside the area of origin?

“Which are of area of origin law? The Delta has one, the San Joaquin has one, there’s a counties area of origin – I mean it’s a bloody mess,” said Phil Isenberg. “I don’t think the area of origin is going to easily turn itself into a water marketing tool. It could, because everybody’s busily involved in trying to find a way when government doesn’t deliver the water that they want, that government has to give them money in exchange. The funny court of claims decision out of the Klamath River, which I know is not really applicable here, was kind of charmingly proof of the fact that smart lawyers are trying to figure out a way to monetize water and one of the ways is to dip your fingers in the taxpayers pocket if you don’t get what you want. But I don’t think the area of origin is likely going to be the predominant tool for that.”

“Which are of area of origin law? The Delta has one, the San Joaquin has one, there’s a counties area of origin – I mean it’s a bloody mess,” said Phil Isenberg. “I don’t think the area of origin is going to easily turn itself into a water marketing tool. It could, because everybody’s busily involved in trying to find a way when government doesn’t deliver the water that they want, that government has to give them money in exchange. The funny court of claims decision out of the Klamath River, which I know is not really applicable here, was kind of charmingly proof of the fact that smart lawyers are trying to figure out a way to monetize water and one of the ways is to dip your fingers in the taxpayers pocket if you don’t get what you want. But I don’t think the area of origin is likely going to be the predominant tool for that.”

Audience question: If you look at the economics of water over hundred years or more, economies of scale have driven what’s happened, because water more than other utilities is marked by economies of scale. What I’m fascinated by is a conscious attempt to push back or to limit the economies of scale to secure other objectives, including trust and ecosystem, because planners have always given into the pressure of economies of scale.

“I agree with you in principle, there are definite limits to economies of scale in water management, and we’re seeing quite a few of them, these days, particularly in storage,” said Jay Lund.

“There have been questions raised about what would the costs savings be if you built one of the proposed tunnels now instead of two; it would not be half the cost, but it would probably be significantly cheaper,” said Ellen Hanak. “We don’t have those numbers now, because in the analyses that the state has done to compare with smaller alternatives, they’ve always looked at building two tunnels but just building two smaller ones. To be sure, building two smaller ones is more expensive, almost no cost savings compared to just build one. The argument has been you need redundancy and so on, but that’s one of the things that merits looking at and it wouldn’t be hard to figure out what that cost would be.”

Audience question (directs to Ellen Hanak): “I’d be interested in how you might compare getting to the grand compromise from where we are today. With the model we have on the Colorado River, where we don’t just have all the complexities within one state, there are seven states, and we have had what can be described as a grand partnership that has existed for almost a century, and that it has worked very well, in spite of having the same types of competing and conflicting uses. Why did that work and why is it so hard to get where you’d like us to go?”

“Where you see really good stuff happening that’s hard in water, it’s usually because people have very strong motivation,” said Ellen Hanak. “That can be because the fear of not compromising is something even worse, and regulatory push can make that happen; fear of regulations being undermined can also make that happen. So maybe we’re at a point where the combination of state and federal agencies being in different places can help push everybody together enough to get a compromise.”

“There’s a wonderful book out now by John Fleck on the Colorado River and its usefully optimistic about how to make those compromises occur,” noted Jay Lund.

Phil Isenberg gave an observation on the John Fleck book. “Although he points out that the world will not come to an end if we start to be more prudent with our use of water, particularly in agriculture, he wrote two articles after the book came out, pointing out that what gives him pause when looking at California is the Salton Sea and the Delta. To me, one of the most interesting ingredients is figuring out why people get exhausted by fighting, and what leads them therefore to another thing. On the Colorado River, I would argue as much as anything, it’s the US Supreme Court. If there is any bigger gorilla in the room then the US Supreme Court and the 1963 Arizona-California decision, I can’t imagine what it is.”

Audience question: “When you were talking about ecosystem management, I thought what you were suggesting was maybe a waiver of the ESA, and I wondered if you could talk more about how you feel the ESA is interfering with ecosystem management.”

“I don’t know whether it’s explicitly would be legally called a waiver – it would be like a pilot project, thinking about having an alternative strategy for conservation of Delta smelt,” said Ellen Hanak.  “We’re at a point now where there are some significant tradeoffs in how you use your environmental water resources. The ESA does not recognize that there are any limits and there isn’t actually a cost effectiveness standard or anything else, but in fact, society is going to end up imposing some kind of limit to how far you can take ESA regulations. For example, if in order to save the Delta smelt you had to empty Lake Oroville, probably there would be some political process to not make that happen, right? So, thinking about the ESA in terms of how to manage environmental resources effectively, it makes sense to think in terms of putting your water and your other environmental resources, applying it in ways that are going to get you the biggest bang for your buck. At this point, having the Delta smelt being a leading species on that, is in fact going to take away resources from doing other good stuff, and that’s less productive, so that’s the idea there. So when we talk about managing for the ecosystem, we’re thinking about where can you get some good functionality that’s going to benefit a number of species and consider some of those tradeoffs, and use some different strategies for Delta smelt.”

“We’re at a point now where there are some significant tradeoffs in how you use your environmental water resources. The ESA does not recognize that there are any limits and there isn’t actually a cost effectiveness standard or anything else, but in fact, society is going to end up imposing some kind of limit to how far you can take ESA regulations. For example, if in order to save the Delta smelt you had to empty Lake Oroville, probably there would be some political process to not make that happen, right? So, thinking about the ESA in terms of how to manage environmental resources effectively, it makes sense to think in terms of putting your water and your other environmental resources, applying it in ways that are going to get you the biggest bang for your buck. At this point, having the Delta smelt being a leading species on that, is in fact going to take away resources from doing other good stuff, and that’s less productive, so that’s the idea there. So when we talk about managing for the ecosystem, we’re thinking about where can you get some good functionality that’s going to benefit a number of species and consider some of those tradeoffs, and use some different strategies for Delta smelt.”

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!